Index

'Property' | Diggers |

Gift | Oppressed |

Fairfax

Land and Freedom

Injustice and the Privatisation of Land in Britain

Charles I: The Commoners' King - halting then reversing

enclosure

Yes... King Charles I was 're-nationalising' newly enclosed land, just before

the English Civil War broke out.

I present here three accounts, from two different books, of pre-Civil War

actions by King Charles I to penalise lords of manors, merchants and other

enclosers. I suggest resentment caused by these retrospective

compositions, or fines, may have been the true reason for acrimony, and

eventually civil war, between England's feudal and merchant classes. It certainly

speaks very well for Charles' record and was largely a result of his good

relationship with Archbishop Laud, who was championing the needs of the new

landless classes within the English government.

I present here three accounts, from two different books, of pre-Civil War

actions by King Charles I to penalise lords of manors, merchants and other

enclosers. I suggest resentment caused by these retrospective

compositions, or fines, may have been the true reason for acrimony, and

eventually civil war, between England's feudal and merchant classes. It certainly

speaks very well for Charles' record and was largely a result of his good

relationship with Archbishop Laud, who was championing the needs of the new

landless classes within the English government.

After the civil war enclosure was greatly accellerated by a landowners

parliament, to blight the entire population to the present day. If the

'compositions' had not been retrospective the merchant class may have put

up with them... but this aspect of Charles' new anti-depopulation and

anti-enclosure fines/laws made the merchant class very angry.

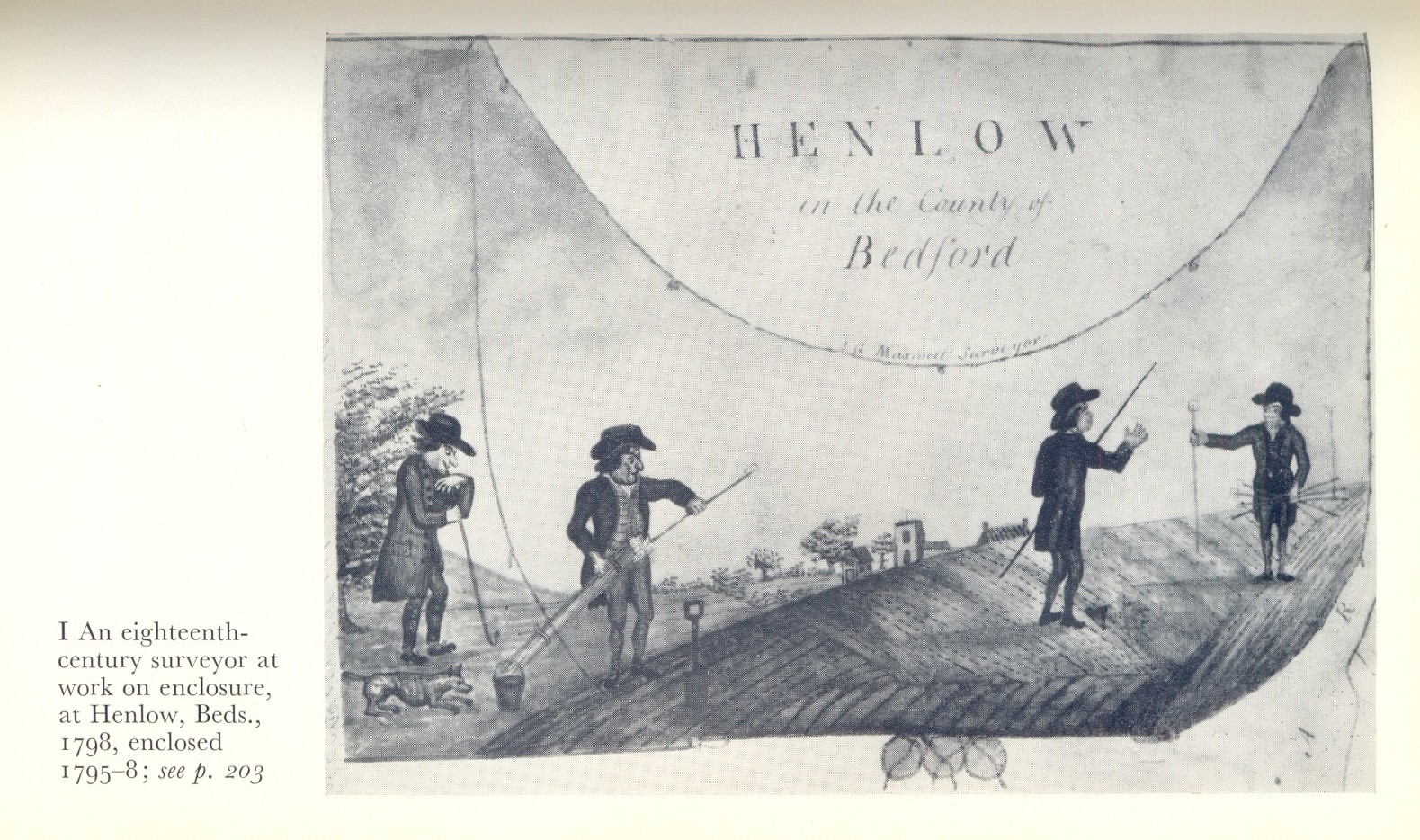

Extract 2 - The English Village Community and the Enclosure

Movements by W. E. Tate, Victor Gollancz, London, 1967 - 'If the reign

in its social and agrarian policy may be judged solely from the number of

anti-enclosure commissions set up, then undoubtedly King Charles I is the

one English monarch of outstanding importance as an agrarian reformer.'

Extract 3 - Common Land and Inclosure, by E. C. K. Gonner.

Macmillan and Co., Limited. St. Martin's Street, London. 1912. - 'In

1633-4 we find a proposal that all inclosures made since James I. should

be thrown back into arable on pain of forfeiture, save such as be compounded

for. The suggestion was not lost sight of, and from 1635 to 1638 compositions

were levied in respect of depopulations in several counties of which an account

is fortunately preserved.' - download

this as a printable Word document with table and footnotes

The Battle of the Braes. Heroic Crofters fight back

against the privatisation of Scottish land in 1882 and bring an end to the

Highland Clearances

English Civil War and the Diggers' Intuition

The Campfire Revolution

by Tony Gosling - June 2009

Squatters are going up market. As liars loans are called in and gangster

capitalists, outside the inner circle, are ejected from their Kitsch mansions,

Mayfair squats are becoming regular news.

In Birmingham 'Justice Not Crisis' are organising waves of group squats matching

homeless people with empty homes and public buildings. From their squatted

Dalston headquarters, Passing Clouds have a minimal overhead business model

for us all … and one of the funkiest clubs in North London. Anticipating

the need for a "money free economy" the squatting group in Bristol have opened

a Free Shop, a High Street version of the internet Free Cycle system. Everywhere

the disposessed and the unsung are refusing to be ruled by a casino elite's

money system.

The twin conundrums of the War of Terror and the Financial Meltdown are making

headlines daily but the real story is how we are responding to the folly

of our ever more secretive, distant and reclusive 'betters'.

This is by no means a NATO zone phenomenon. Churches in Mumbai, India have

been buying tracts of arable land outside the city, handing it to unemployed

urban families, and creating egalitarian villages from the ground up. They

have called the latest Muktapur, 'Salvation Village'.

Even the vision of what kind of Ecological new build we need to downshift

our post industrial nation is being hotly challenged. Is it to be Prince

Charles' £250k stone cladding Poundbury? A Persimmion EcoVillage? An

elitist pseudo revolution is being prepared for us, signed off by 'The Borg'.

An epic struggle is unfolding between ruddy-faced peasant activists and elitist

accountants. Between profit margins and common sense. Between whether the

land is a commodity to be traded like barrels of oil on the open market or

a fundamental human right. It's unlikely to be pretty.

With justice, peace and with peace, beauty. Visions for a just future are

being hotly contested around the campfire. Can ecological justice accommodate

private banking? Or the soulless legal 'person' of the Corporation? Can there

be any hint of justice with war criminals in government? How utterly sunk

is the media? How best to organise?

The G20s greatest financial confidence trick in history looks sure to bring

all these issues to a head, to our doors. A new generation of Levellers,

Ranters and Diggers are rising to the challenge.

Meanwhile new light is being thrown on the true origins, in the 1630s, of

England's first Civil War. Historian W. E. Tate points out that Charles I

acted decisively to make enclosure 'depopulation' a criminal offence.

'From 1635-8 enclosure compositions [fines] were levied in thirteen counties,

some six hundred persons in all being fined, and the total fines levied amounting

to almost £50,000. Enclosers were being prosecuted in the Star Chamber

as late as 1639.'

Though he may not have had the detail, it seems Gerrard Winstanley and his

Diggers were right, recklessly lucrative land privatisation of Cromwell's

merchant class was at the heart of the seven year struggle. Revolution it

was not.

Quite whether our present struggle pans out to such extremes of the BBC's

1975 series 'Survivors' God only knows, but it will be the severest test

yet of our ability to work together. To open meetings and pause before big

decisions in silence or prayer will ensure we don't lose sight of the spiritual.

We all have a part to play on the way to the first Quaker George Fox's vision

of 'a thousand points of light'. "Whether England shall be the first Land,

or some others, wherein Truth shall sit down in triumph."

* The English Village Community and the Enclosure Movements by W. E. Tate,

Victor Gollancz, London, 1967. p. Chapter 11, Enclosure and the State: (A)

In Tudor and Early Stuart Times.

[nb. this article was commissioned by Simon Fairlie for 'The Land' magazine

in May 2009 but he subsequently turned it down]

Manors, Fields and Flocks: Farming in Medieval England

Manors, Fields and Flocks: Farming in Medieval England

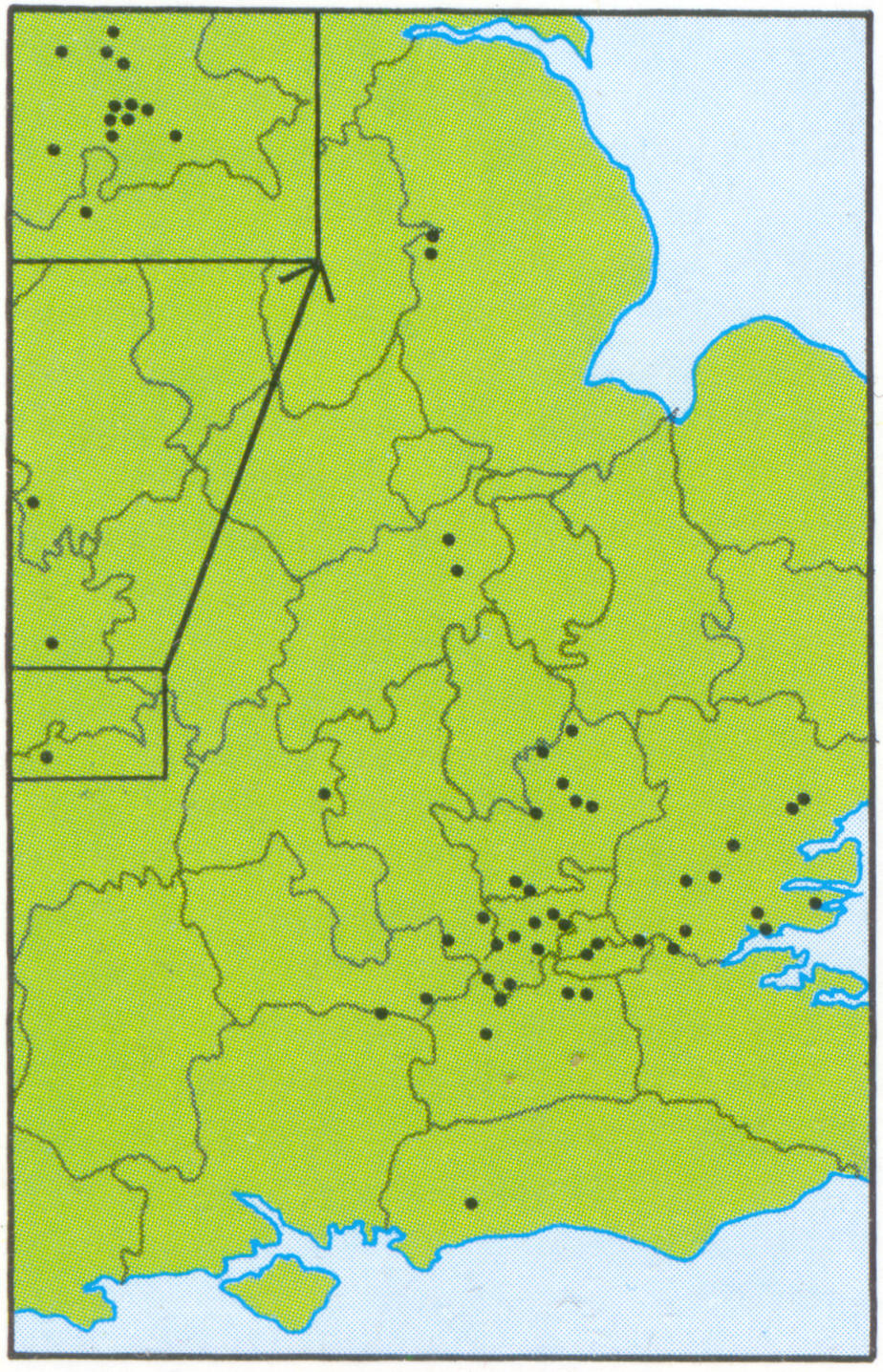

Manors belonging to Westminster Abbey in 1086.

The map shows how widespread the distribution of a

great ecclesiastical estate's possession could be.

Extracted from:-

The Historical Atlas of Britain

by Malcolm Falkus and John Gillingham

Published in 1981 by Granada

ISBN 0 246 11614 5

Manors, Fields and Flocks: Farming in Medieval England

The estate or fief was the unit of large-scale exploitation supporting the

ruling class, and the manor was the constituent cell of which the fiefs and

estates were composed. Each manor in turn consisted of land called the demesne,

which could be managed and cultivated directly by the lord, and land in the

hands of rent-paying tenants, predominantly in small plots.

Two types of manorial settlement

and cultivation. At Wigston Magna in Leicestershire, good-quality land was

farmed on the three-field system from a central settlement.

Two types of manorial settlement

and cultivation. At Wigston Magna in Leicestershire, good-quality land was

farmed on the three-field system from a central settlement.

If we examine the manor in detail we soon find that it displayed an almost

infinite variety of structures, each one dependent upon a wide range of

jurisdictional, topographical and agricultural variables.. Yet there were

a number of common features which assist the grouping of manors into broad

categories. Most notably we have manors with nuclear or with scattered

settlement, and this distinction went hand in hand with either strip farming

in open fields or with the cultivation of small enclosures. Two examples

illustrate these two main forms of manorial and farming structure. Wigston

Magna in Leicestershire was an open-field village of the classic type, and

its three great fields remained virtually unchanged until 1776. The bulk

of the 70 or more families in medieval Wigs ton lived in cottages lining

the two main streets, close to the village green and between the two churches.

The lands held by each family would be scattered in small strips, often of

an acre or less, in the three fields. By contrast, the upland terrain of

Cornwall was ill-suited to open-field farming and tightly clustered villages.

At Stoke Climsland in the east of the county we find the 100 or more families

on the manor living in scattered hamlets and cultivating compact enclosed

pieces of land. There were over 40 different settlements, and they were

interspersed with expanses of rough pasture and unimproved downland.

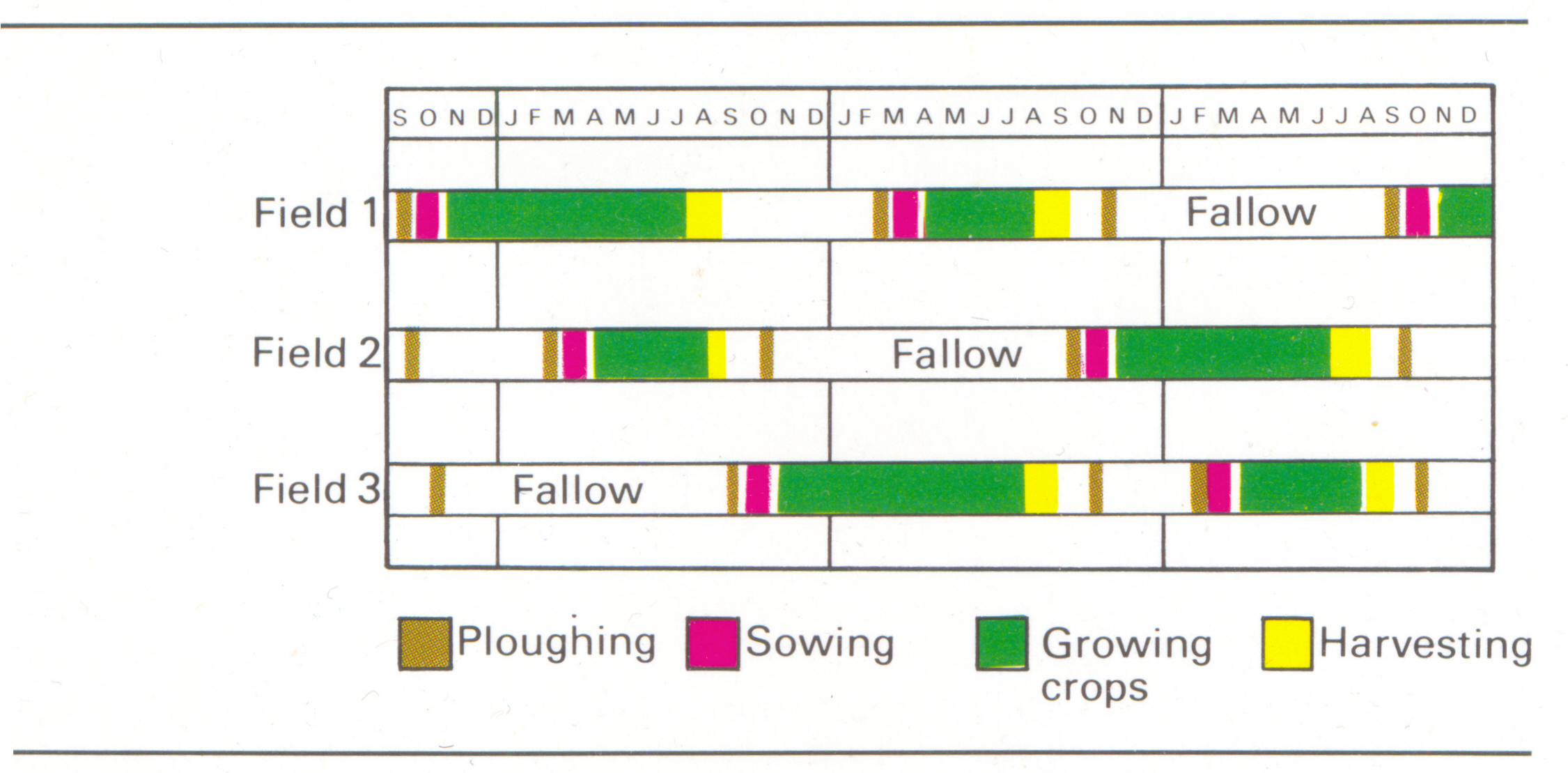

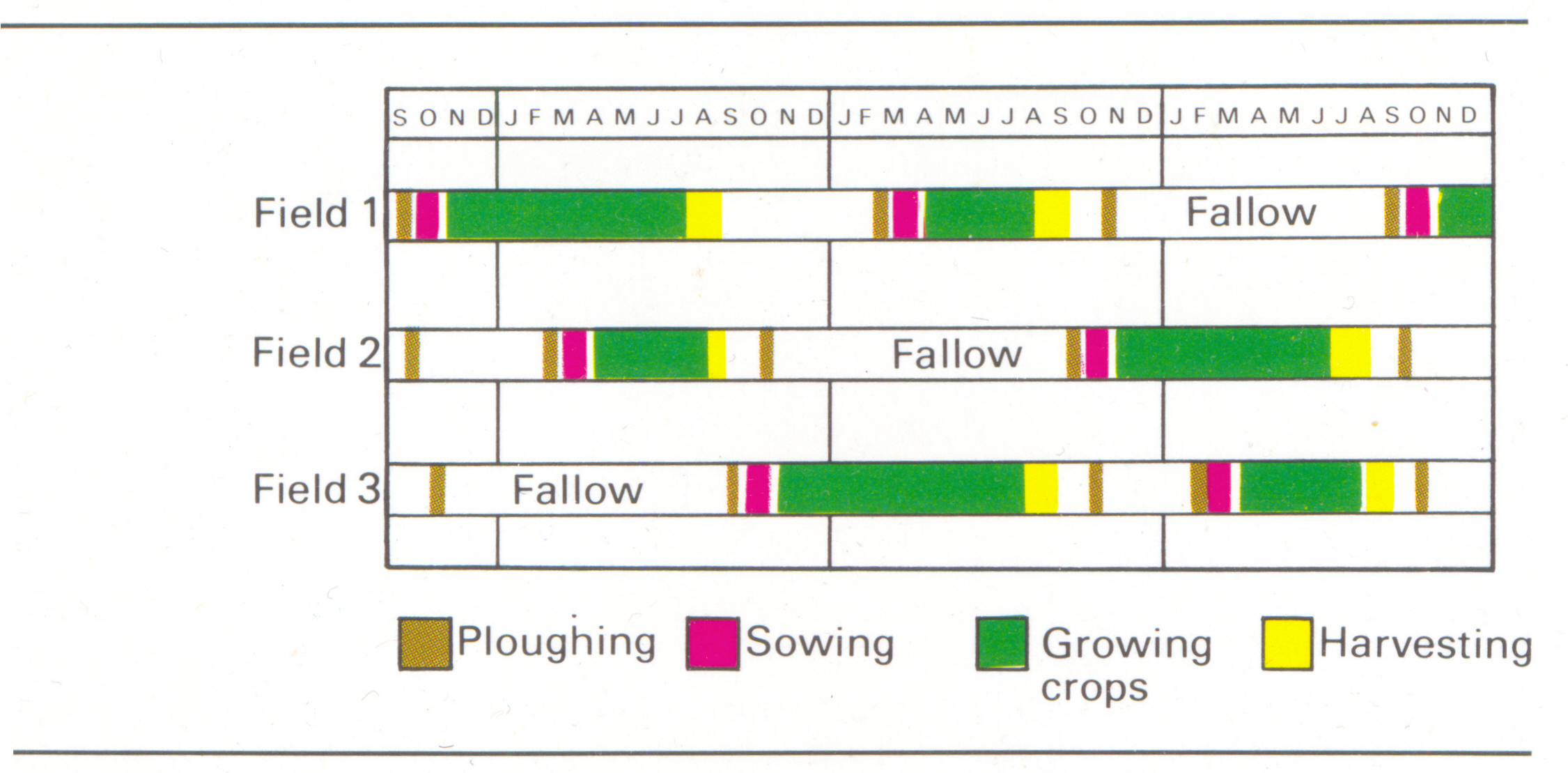

In open-field villages the freedom of the individual farmer was limited by

the need to conform to communal routine, for his lands were intermingled

and interlocked with those of other tenements. Under an orthodox, three-field

system, each field would experience a three-year rotation consisting of

winter-sown crops (wheat and rye), spring-sown crops (oats or barley) and

fallow.

The cultivation of small enclosed

fields by individual families could by contrast be very flexible. Generally

enclosures were prominent in hilly terrain and where land was being taken

in small parcels from moorlands, woodlands, and marshlands. Often convertible

husbandry was pursued, in which the plots were subjected to rotation of crops

followed by a number of years under grass. The length of the grain and grass

cycles could be altered to suit the needs of the farmer and the quality of

the soil; moreover, the rotation helped to improve both crop yields and the

quality of pasture.

The cultivation of small enclosed

fields by individual families could by contrast be very flexible. Generally

enclosures were prominent in hilly terrain and where land was being taken

in small parcels from moorlands, woodlands, and marshlands. Often convertible

husbandry was pursued, in which the plots were subjected to rotation of crops

followed by a number of years under grass. The length of the grain and grass

cycles could be altered to suit the needs of the farmer and the quality of

the soil; moreover, the rotation helped to improve both crop yields and the

quality of pasture.

Two types of manorial settlement and cultivation. At Stoke Climsland in

Cornwall more marginal land led to a pattern of scattered settlements.

Although there were some places, especially in the remote colonizing frontiers,

where fields were of minor importance and enterprise was primarily pastoral,

mixed farming predominated throughout most of England. Consequently, the

right to pasture animals on village fields and wastes was highly prized.

Even in those regions particularly suitable for arable, beasts had to be

reared to draw ploughs and carry produce and people and, of course, livestock

was essential to arable farming as the prime source of fertilizer. Most peasants

aspired to possess plough-beasts, and a few cows, pigs, sheep and poultry,

though their limited resources usually meant that they attained far less.

Landlords, however, frequently built up large herds and vast flocks. During

the wool-production boom of the 13th century a large number of estates kept

flocks of many thousands of animals. In Edward 1's reign the export trade

alone absorbed the fleeces of eight million sheep a year.

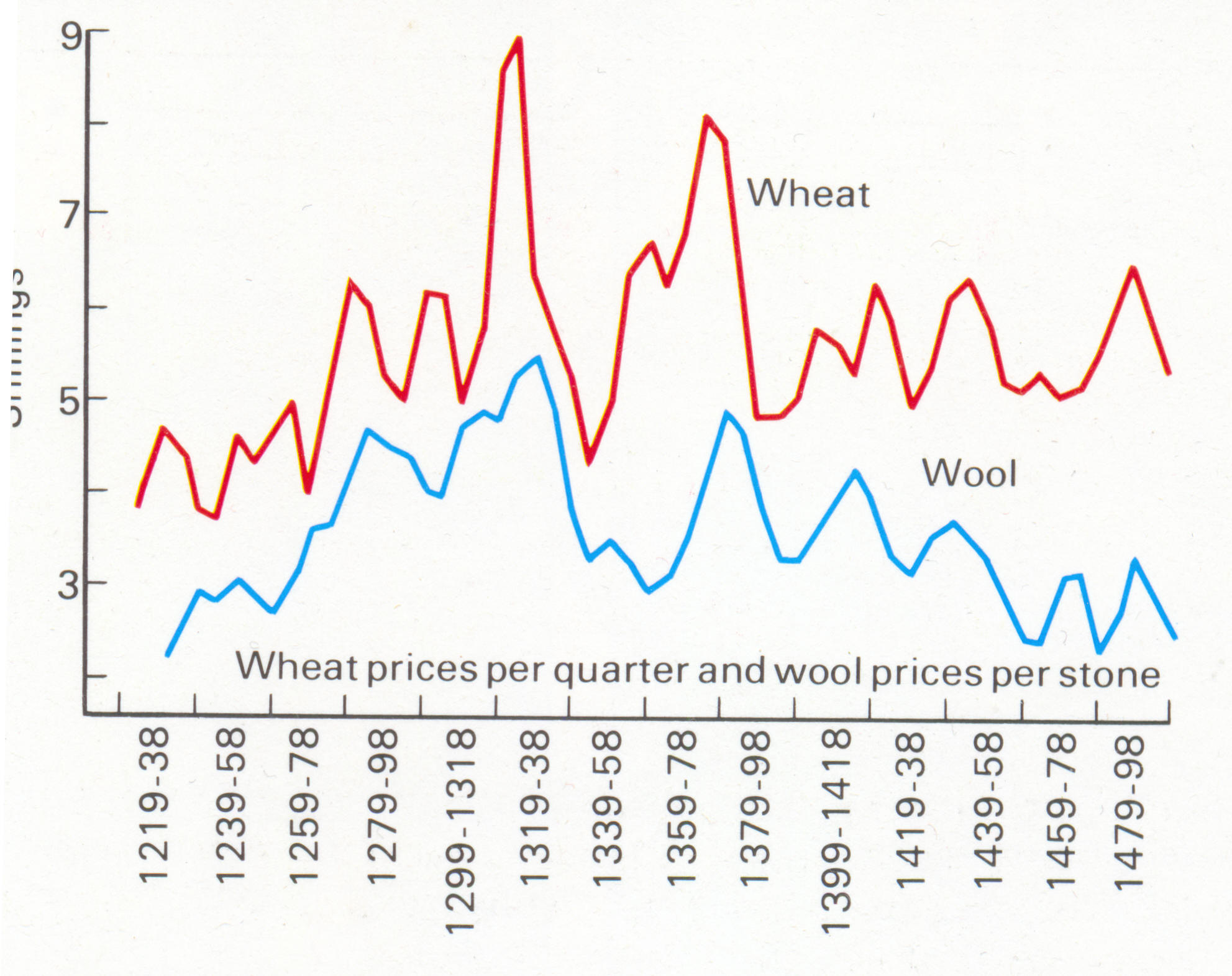

English wool was among the finest in Europe. The diagram provides a guide

to the relative quality of the wool produced throughout the country in the

first half of the 14th century. Altogether the prices fixed in 1343 relate

to over 50 different grades of wool, varying in price from £9. 7s. 6d.

a sack down to £2. 10s. 0d. At one end of the spectrum we have the very

best wool from the Shropshire and Herefordshire borderlands, followed by

fine fleeces of Lindsey and the Cotswolds, and at the other end we have Cornish

wool, described contemptuously by contemporaries as 'Cornish hair'.

The

operation of the classic open field system.

The

operation of the classic open field system.

Landlords untroubled by the stark struggle for subsistence which characterized

peasant farming, had much greater freedom of choice as to how to manage the

land which they controlled directly, their demesnes. While one choice was

the balance between arable and pastoral, a more fundamental choice was between

direct exploitation and leasing. The 13th century, with its strongly rising

prices for agrarian produce and cheap labour, was the age of direct management,

the age, as it is called, of 'high farming', when landlords marketed increasing

quantities of grain, dairy produce and wool. The 14th century, with its famines

and plague, was a far more difficult period for the large-scale farmer. But

it was not until the last quarter of that century that prices turned decisively

downwards. Thereafter, falling prices for both grain and wool, combined with

rising wages and associated labour problems, undermined demesne profits and

encouraged leasing.

By modern standards, yields in the

Middle Ages of both arable and livestock husbandry were low. Even the rather

optimistic estimates of contemporary farming treatises put the return of

oats at around only four-fold the seed sown, wheat five-fold, and barley

eight-fold. The average yields actually achieved on the extensive demesne

farms of the Bishops of Winchester never approached even these modest targets.

At these levels wheat and barley would have yielded less than one-third of

today's crops, and oats less than one-fifth. A variety of measures were taken

to improve returns, including in many places the digging in of marl and seaweed.

Many villages also switched from a two-field regime, in which half the land

lay fallow each year, to a three-field system, but the adoption of legumes,

which improved fertility by fixing nitrogen in the soil, was not rapid. It

is possible that, in comparison with modern standards, livestock farming

was relatively more efficient than arable.

By modern standards, yields in the

Middle Ages of both arable and livestock husbandry were low. Even the rather

optimistic estimates of contemporary farming treatises put the return of

oats at around only four-fold the seed sown, wheat five-fold, and barley

eight-fold. The average yields actually achieved on the extensive demesne

farms of the Bishops of Winchester never approached even these modest targets.

At these levels wheat and barley would have yielded less than one-third of

today's crops, and oats less than one-fifth. A variety of measures were taken

to improve returns, including in many places the digging in of marl and seaweed.

Many villages also switched from a two-field regime, in which half the land

lay fallow each year, to a three-field system, but the adoption of legumes,

which improved fertility by fixing nitrogen in the soil, was not rapid. It

is possible that, in comparison with modern standards, livestock farming

was relatively more efficient than arable.

Agricultural prosperity: wool prices in England in 1343, shortly

before the first outbreak of the Black Death. Contemporaries were well aware

of the value of English wool: 'half the wealth of the kingdom' was. how one

of them described it in the late 13th century.

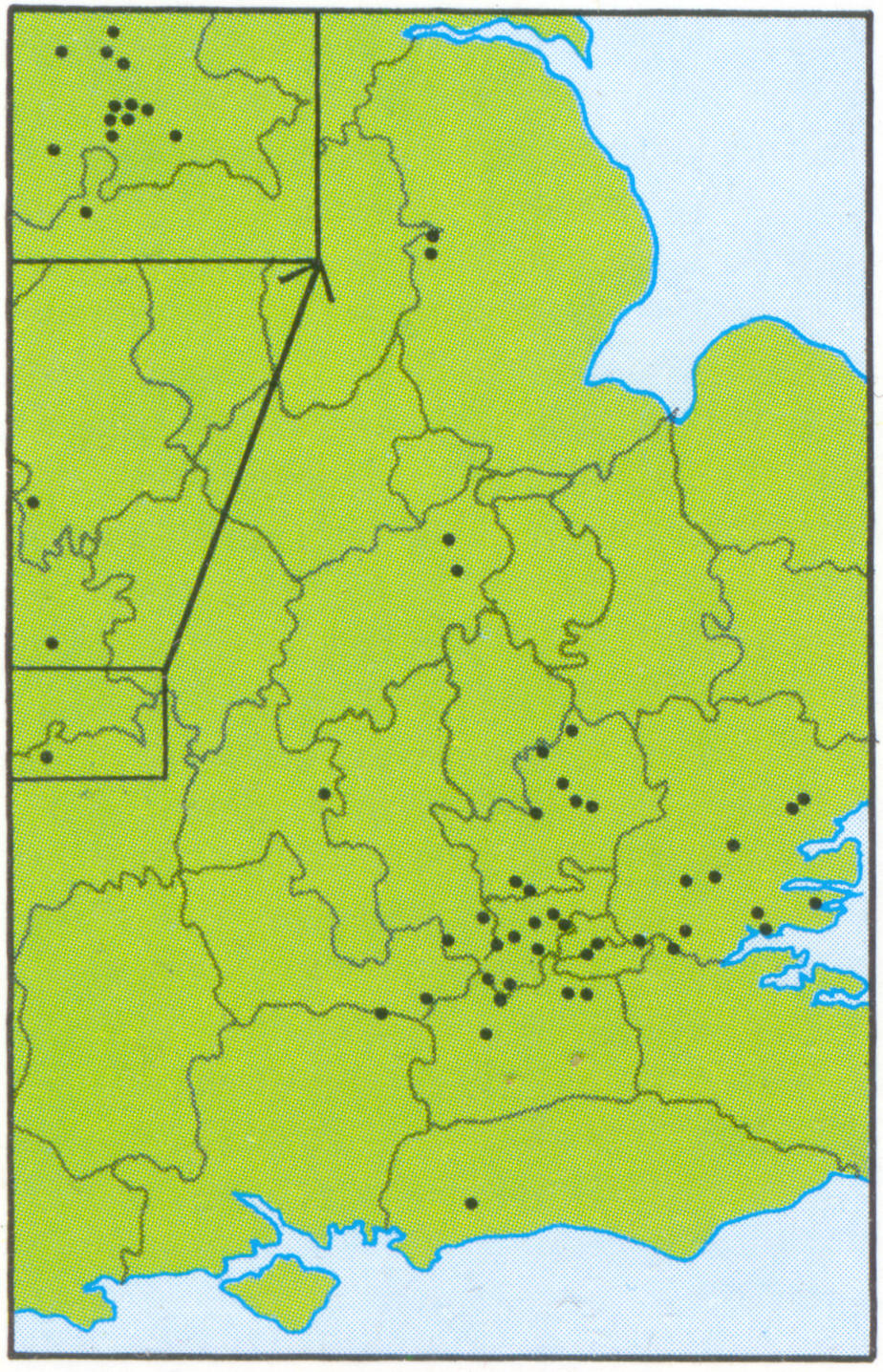

Land Enclosure

The adoption of enclosure, associated with improved crop rotations, was perhaps

the single most important development in agriculture. Whatever advantages

the open fields may have had for the communities which farmed them in earlier

centuries, the greater efficiency and productivity of enclosed land ensured

a progressive abandonment of the open-field system. Nonetheless, looked at

over the centuries, progress was relatively slow. Open fields seem always

to have been less in evidence in the Highland Zone of the North and in the

South-West, in Wales, in Kent, and parts of Essex and in those areas where

land had been reclaimed from forest, waste and marsh. In later medieval and

early modern times enclosure of fields and commons for both pasture and arable

progressed even further in these regions, as well as in others where open

fields had predominated. The later 15th century was a period of widespread

enclosure for pasture, and in the following two centuries we can discern

that the progress of enclosures was most rapid in the North-West, the Welsh

borders, the Vales of Gloucester and Glamorgan, the north-west Midlands,

west Yorkshire, and parts of Norfolk, with each region adopting the type

of enclosure best suited to its needs (see p. 185). By the later 17th century

the greater part of land was enclosed in northern and western regions, and

in the South East; but open fields were still dominant in a broad swathe

of central England. Attention must also be drawn to the other major agricultural

'improvement', engrossment. The concentration of land into larger farms and

the decline of the smallholder were to be powerful forces in raising agricultural

efficiency.

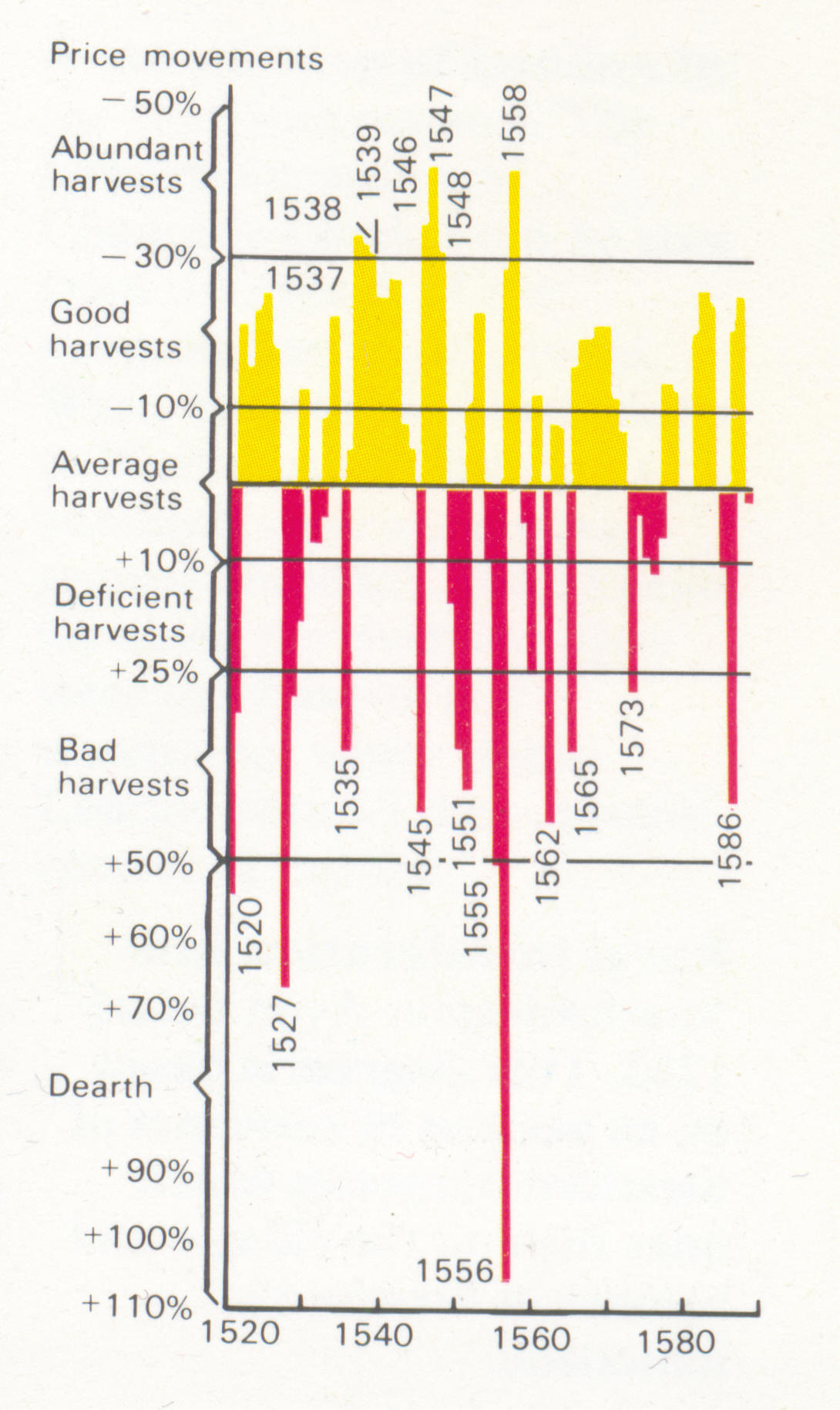

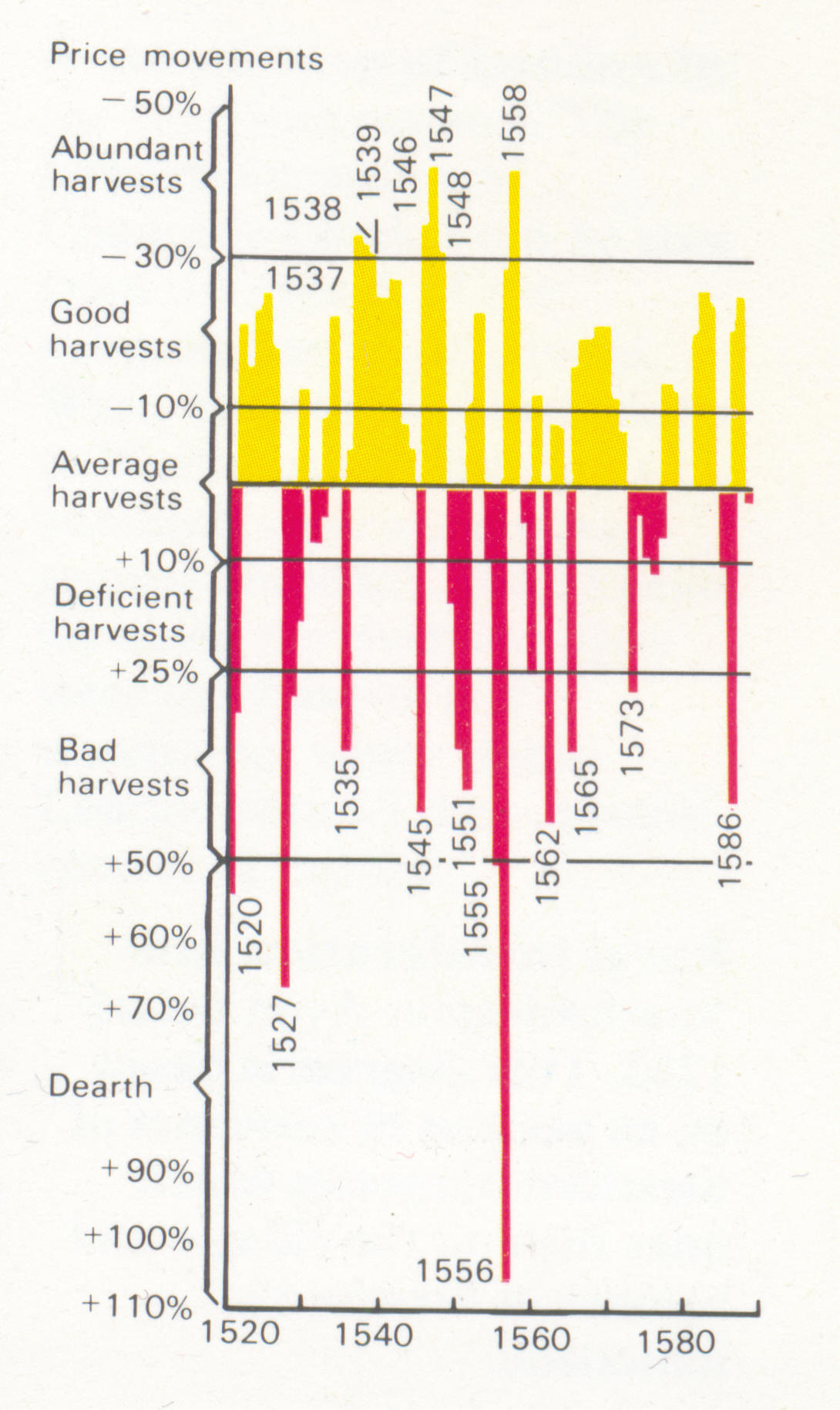

Grain price movements, 1520-90. Prices

oscillated wildly as yields fluctuated. Until the great agrarian improvements

of later centuries, and the development of an international trade in foodstuffs,

all sectors of the economy were deeply affected by the quality of the

harvest.

Grain price movements, 1520-90. Prices

oscillated wildly as yields fluctuated. Until the great agrarian improvements

of later centuries, and the development of an international trade in foodstuffs,

all sectors of the economy were deeply affected by the quality of the

harvest.

It was only after long centuries of agrarian improvement and the opening

up of international trades in foodstuffs on an unprecedented scale, that

the dependence of Englishmen and women upon the state of the harvest was

substantially lessened. During the medieval and early modern centuries the

quality and quantity of the harvest was of paramount importance to the whole

population and to all sectors of the economy. A poor harvest meant that

smallholders had less to eat; a bad harvest forced them to purchase food

in order to survive, and might also entail the sale or slaughter of essential

livestock. Poor yields also meant high prices, so that all those who had

to buy food were left with less money to spend on manufactures and non-essential

items. Thus harvest failures not only struck rural communities; they adversely

affected craftsmen and merchants. The harvest was at the very heart of the

economy and its health was determined by the vagaries of the weather. Prices

oscillated wildly as yields fluctuated. Such instability severely limited

the potential for development and progress in the nation's economy.

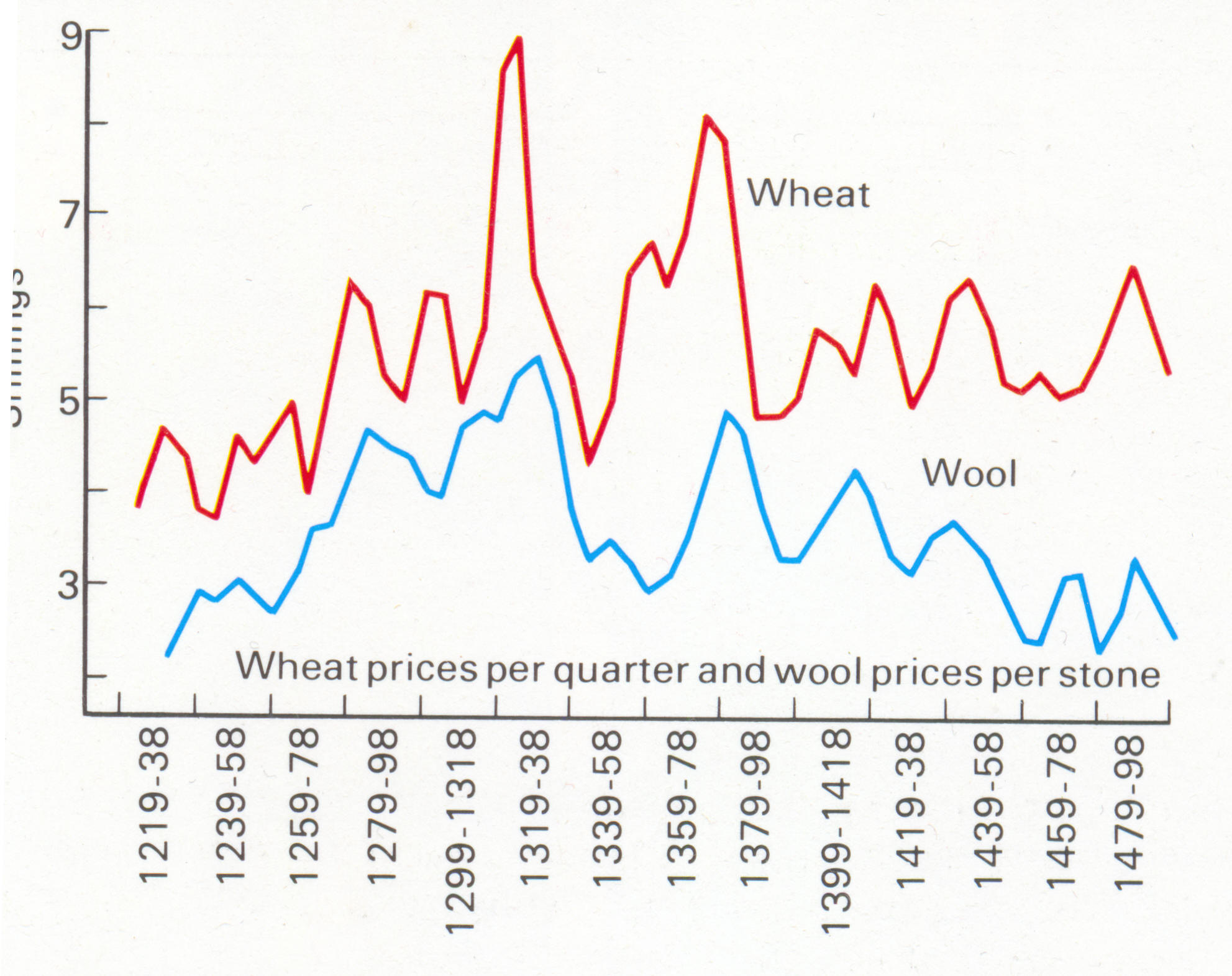

The underlying trends revealed by this graph show steadily rising prices

both for wheat and wool during the 13th century followed by a period of stable

or declining prices in the following two centuries.

Extracted from:-

The Historical Atlas of Britain

by Malcolm Falkus and John Gillingham

Published in 1981 by Granada

ISBN 0 246 11614 5

Manors, Fields and Flocks: Farming in Medieval England

Living on the wasteland

C18 Encyclopedia Brittania definition of the English word 'dole':

'A part or portion, most commonly of a meadow, where several persons have

shares.'

Tony Gosling - April 1999

We're not talking about living on managed nature reserves - the fact is that

high-impact land use (intensive housing and chemical farming)- combined with

a lack of public access (scrutiny) leads to practices far more detrimental

to biodiversity.

You have to be very careful using arguments about exclusivity of access to

land - eg. this piece of land is for plants only. I remember seeing

an Englishman in Scotland getting a cool reception in 1997 when he unveiled

plans for a people-free wildlife area in the Cairngorms, "I'd say ye have

nae spoken wi' many local people. Have ye never heard of the clearances,"

was the frosty reply.

The point we're trying to make is that responsible people manage land for

the benefit of all species - not to the exclusive benefit of man. I believe

Simon's criteria has a section where biodiversity is mentioned as having

to form part of any management plan. That is to say "if you ain't gonna improve

biodiversity you can't have your planning permission"!

I think it's really important to get away from the idea that man is incompatible

with other species. It doesn't have to be like that! The problem is the current

attitude to land which so many farmers have which is that they see it as

their factory floor and don't look at WHY it is necessary or lucrative for

them to use chemicals and force land into monoculture.

The reasons for this have a lot to do with EEC subsidies and modern distribution

networks. But many farmers, and others, are guilty of this partitioned thinking

where they have a 'resigned' attitude to the structure which is forcing tenant

and landowning farmers to intensify their activities to destructive proportions.

The other problem comes from the private ownership of land. This means if

there is any dispute about what should happen or not be allowed on the land

there is no reason to talk to your neighbours. You just do what you want.

It is also a very important concept that the earth is a free gift to mankind.

Not to one class of mankind and not another.

Sharing land forces us to justify our plans in front of the local community

and forces us into a much-needed participatory approach to land use/management.

If a modern day village was to be told the inhabitants were collectivising

the land there would be nothing less than the screaming ab-dabs!!

People get very territorial especially when they have been able to wangle

more than their fair share. But eventually agreement would be reached...

see Ken Loach's film 'Land and Freedom' for an example of this happening

in the Spanish Civil War.

But look at a pre-inclosure village. It would look something like the New

Forest where the land is managed by local agreement and by local consensus.

No wonder the rich and powerful sought fit to inclose it because the local

wouldn't agree to their wishes to ruin it!!!

There is now only one wholly unenclosed village in the country, Laxton in

Nottinghamshire.

Try visiting Laxton or the New forest and tell me if unenclosed land and

wasteland is incompatible with people. You'll find in both these places

the people are a positive benefit to the area.

Charles I: The Commoners' King

"From about 1607 to 1636, the Government pursued an active anti- enclosure

policy" - W.E. Tate

Charles' anti-enclosure policies may have been the spark that ignited the

English Civil War

Extract 1

Historians are inconclusive about the origin and cause of the war. Whatever

brought the merchant classes, or bourgeoisie, to armed conflict with the

landed feudal gentry, personified by the king, must have had a mighty incentive.

Driven by the new capitalist class the move from collective to private ownership

of land was extremely lucrative. To halt it, unforgivable. In the eyes

of the avaricious merchants the king had to go!

Extract from: 'The English Village Community and the Enclosure

Movements'

W. E. Tate, Victor Gollancz, London, 1967. (longer extract

below)

Chapter 11

Enclosure and the State in Tudor and Early Stuart times.

The Policy of the Early Stuart Governments

Probably in Stuart times baser motives weighed more heavily with the governmental

authorities. The Stuart policies, especially that of Charles I, were as Tawney

says, 'smeared with the trail of finance'.,' Enclosure, at any rate enclosure

leading to depopulation, was an offence against the common law."* Commissions

inquired into it, and in many cases the statesmen and divines who composed

these were inspired by the loftiest motives. The general action of the

government, however, was to use the Privy Council and the courts, especially

the prerogative courts, the Court of Requests and the Star Chamber, the Councils

of Wales and the North, as means of extortion. The offenders were 'compounded

with', i.e. huge fines were levied so that the culprits might continue their

malpractices.¹

In 1601 a proposal to repeal the depopulation acts was crushed upon the ground

that the majority of the militia levies were ploughmen.² In 1603 the

Council of the North were ordered to check the 'wrongful taking in of commons'

and the consequent 'decay of houses of husbandry . . .'. From about 1607

to 1636, the Government pursued an active anti- enclosure policy.³ In

1607 the agrarian changes in the Midlands had produced an armed revolt of

the peasantry, beginning in Northamptonshire, where there had been stirrings

of unrest at any rate since 1604. The counties mainly affected were

Northamptonshire, Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Huntingdonshire, Leicestershire,

the three divisions of Lincolnshire, and Warwickshire.

The leader was a certain John Reynolds, nick- named Captain Pouch, 'because

of a great leather pouch which he wore by his side, in which purse he affirmed

to his company there was sufficient matter to defend them against all commers,

but afterwards when he was apprehended, his Pouch was searched, and therein

was only a peece of greene cheese'. John was soon dealt with after a skirmish

at Newton, where a body of mounted gentlemen with their servants dispersed

a body of a thousand rebels, killing some forty or fifty of the poorly-armed

rustics. Some of his followers were hanged and quartered.

Promises of redress made by various proclamations were fulfilled only to

the extent of the appointment of still another royal commission to inquire

into agrarian grievances in the counties named. After it had made its return,

however, it was discovered that on legal technicalities the commission was

invalid, and little action seems to have been taken upon its laboriously

compiled returns. The local gentry were soon busily at work again in enclosing

their own land and that of others, though in 1620 Sir Edward Coke, the greatest

of English judges, who had already shown himself a keen opponent of enclosure,

declared depopulation to be against the laws of the realm, asserting that

the encloser who kept a shepherd and his dog in the place of a flourishing

village community was hateful to God and man.

A reaction set in when in 1619 there were good harvests, and the Privy Council

was concerned to relieve farmers and landlords who were suffering through

the low price of corn. This is why commissions were appointed to grant pardons

for breaches of the depopulation acts, and why in 1624 all save the two acts

of 1597 were repealed. The county justices still, however, attempted to check

the change, and in this received more or less spasmodic pressure from the

Council. In the 1630's corn prices rose again, and in 1630 the justices of

five Midland counties were ordered to remove all enclosures made in the last

two years. In 1632, 1635, and 1636 more commissions were appointed, and the

justices of assize were instructed to enforce the tillage acts. In 1633 they

were cited before the Board to give an account of their proceedings. From

1635-8 enclosure compositions were levied in thirteen counties, some six

hundred persons in all being fined, and the total fines levied amounting

to almost £50,000. Enclosers were being prosecuted in the Star Chamber

as late as 1639. However, the Star Chamber was to vanish in 1641, and the

Stuart administrative policy disappeared with the engines by which it had

been - somewhat ineffectively and spasmodically - put in force.

If the reign in its social and agrarian policy may be judged solely from

the number of anti-enclosure commissions set up, then undoubtedly King Charles

I is the one English monarch of outstanding importance as an agrarian reformer.

How far his policy was due to genuine disinterested love of the poor, and

how far it followed from the more sordid motive of a desire to extort fines

from offenders, it is difficult to say. But even the most unsympathetic critic

must allow a good deal of honest benevolence to his minister Laud, Archbishop

of Canterbury, and some measure of it to his master. On the whole it is perhaps

not too much to say that for a short time after the commissions issued in

1632, 1635, and 1636, Star Chamber dealt fairly effectively with offenders.

The lack of ultimate success of this last governmental attempt to stem the

tide of enclosure was due, no doubt, partly to the mixture of motives on

the part of its proponents. Still more its failure is to be attributed to

the fact that again the local administrators, upon whom the Crown depended

to implement its policy, were of the very [landed] class which included the

worst offenders. A (practising) poacher does not make a very good gamekeeper!

The Commonwealth

During the Commonwealth there was little legal or administrative attempt

to check enclosure of open fields. It is not clear how far this was taking

place, though there was great activity in the enclosure and drainage of

commonable waste. Some of the Major-Generals, especially Edward Whalley,

held strong views upon agrarian matters, and attempted to use their very

extensive powers to carry their ideals into operation. Petitions were prepared

and presented, a committee of the Council of State was appointed and numerous

pamphlets were written.

In 1653 the mayor and aldermen of Leicester complained of local enclosures

and sent a petition to London, very sensibly choosing their neighbour, John

Moore, as its bearer. Appar- ently it was because of this that the same year

the Committee for the Poor were ordered 'to consider of the business where

Enclosures have been made'. The question arose again in 1656 when Whalley,

the Major-General in charge of the Midlands, set on foot local inquiries,

and took fairly drastic action in response to petitions adopted by the grand

juries in his area. He hoped that as a result of his action 'God will not

be provoked, the poor not wronged, depopulation prevented, and the State

not dampnified'. The same year he brought in a Bill 'touching the dividing

of commons', but it failed through the opposition of William Lenthall, the

Master of the Rolls, and indeed was not even given a second reading. This

was the last bill to regulate enclosure. Ten years later, in 1666, another

bill was read in the Lords, to confirm all enclosures made by court decree

in the preceding sixty years. It also was unsuccessful, but the fact that

it was introduced is indicative of a great change in the general attitude

towards enclosure displayed by those in authority.

Footnotes:

* Coke (Chief justice of the King's Bench, 1613-16), was very emphatic on

this, Institutes III, 1644 edn., p. 205. Ellesmere, his great rival (Lord

Chancellor 1603-16), was more favourably disposed to enclosure, and himself

authorised some enclosures by Chancery Decree. The point is of interest,

since it may well have been Ellesmere's attitude which emboldened his kinsmen,

Arthur Mainwaring, to embark on the enclosure of Welcombe, near Stratford,

in 1614. In the story of this, Shakespeare plays a (very minor) part. Tothill,

W., Transactions of the Court of Chancery etc., 1649, edn. 1827, P. 109,

and Ingleby, G. M., Shakespeare and the Welcombe Inclosure, 1885.

¹ There is a tabular statement of the proceeds in Gonner, p. 167 [and

presented below!].

² See D'Ewes, op. cit., p. 674, for Cecil's speech on this.

³ The activity was mainly 1607-18 and 1636, the first spasm being due

presumably to the Midland riots, the second to a period of high corn prices.

Extract 2 - 'If the reign in its social and agrarian policy

may be judged solely from the number of anti-enclosure commissions set up,

then undoubtedly King Charles I is the one English monarch of outstanding

importance as an agrarian reformer.'

Extracted from

The English Village Community and the Enclosure Movements by W. E. Tate,

Victor Gollancz, London, 1967

Chapter 11, Enclosure and the State: (A) In Tudor and Early Stuart Times

The Tudor Governments

From the social and political points of view too the Tudor governments disliked

such enclosures as led or threatened to lead to depopulation. Several of

the Tudor rulers, certainly Henry VIII and the Lord Protector Somerset, had

a quite genuine desire to be fair to the small proprietor, who was usually,

with good reason, bitterly opposed to enclosure. All had a lively apprehension

of the danger of dynastic or religious rebellion, and all were unwilling

that malcontents should be presented with the opportunities afforded by the

existence of a dispossessed and starving peasantry. Even before Henry VIII's

time anti-enclosure measures had been placed on the statute book, and throughout

Tudor times there was a long stream of statutes, proclamations and commissions,

all designed to check a process felt to be utterly destructive of the common

weal. Thus in 1517 there was the commission already referred to. Thirty-two

years later a main count in the indictment against Somerset, under which

at last he lost his head, was that he had been so slack in suppressing Kett's

Rebellion in 1549 as to give the rebellious peasantry an idea that he was

in sympathy with their feelings on the agrarian grievances which had led

to the disturbance.

The first landmarks in the story of enclosure in Tudor times are the Depopulation

Act of 1489 'agaynst pullying doun of Tounes', a proclamation of 1515 against

engrossing of farms, and certain inquiries by the justices, etc., made the

same year. A temporary act of early 1516 was virtually made permanent later

in the year, and the next year was the commission of 1517, addressed to the

nobles and gentry of all save the four most northerly counties of England,

with other anti-enclosure commissions in 1518 and 1519. In 1519 Wolsey, as

Chancellor, ordered that those claiming the royal pardon for enclosure should

destroy the hedges and ditches made since 1488. A proclamation of 1526 made

a similar order. There was an act for restraining sheep farming in 1534,

and two further depopu-lation acts in 1536. At the same time proceedings

were taken in the Chancery and the Court of Exchequer against enclosers,

sometimes those of lofty station. Evidently the acts and pro-clamations were

little observed, and in 1548 the Protector Somerset issued yet another

proclamation. A movement in the reverse direction was made in 1550, when

as part of the policy of the nobility and gentry who had triumphed over him,

the Statutes of Merton and Westminster 112 were confirmed and re-enacted,

and measures were taken to check hedge and fence-breaking. However, only

two years later another depopulation act was passed, in 1552.

There was still another in Philip and Mary's time, 1555, and one five years

after Elizabeth I's accession, in 1563. This repealed as ineffectual the

three latest depopulation acts, of 1536, 1552, 1555 but re-enacted the earlier

one of 1489. It was repealed in part in 1593. Most of these acts endeavoured

to re-establish the status quo, to forbid under penalty of forfeiture the

conversion of arable to pasture, and to compel the rebuilding of decayed

houses, with the reconversion to arable of pasture which had lately been

put down to grass. Probably the multiplicity of acts is an indication of

their ineffectiveness. The reason was that the administration alike of acts

and commissions was largely in the hands of the landed classes profiting

by agrarian change. In 1589 was passed Elizabeth's famous act prohibiting

the erection of any cottage without four acres of arable land [? and of course,

proportionate pasture rights]. This remained in force, theoretically at any

rate, until 1775. The difficulty with which the government was faced is well

illustrated by two acts of 1593, which passed through Parliament together,

and which in fact stand next to one another on the statute book, but which

adopt markedly contrasting points of view towards enclosures of different

kinds. The first of them, as noted above, repeals much. of the 1563 act,

that part forbidding the conversion of arable to pasture. The second of them

anticipates legislation of the nineteenth century. It orders that no persons

shall enclose commons within three miles of the City of London, 'to the hindrance

of the training or mustering of soldiers, or of walking for recreation, comfort

and health of Her Majesty's people, or of the laudable exercise of shooting.

. .' etc.

The last Depopulation and Tillage Acts

The more complacent attitude towards enclosure evidenced by the first of

the 1593 acts did not last very long. In 1597 were passed two acts, again

neighbours on the statute book, the first for the re-erection (though with

some qualifications) of houses of husbandry which had been decayed. At the

same time the government clearly recognized that if it merely tried by

legislation to maintain or to restore the status quo, its efforts would be

in vain. So the same act specifically authorizes lords of manors, or tenants

with their lord's consent, to exchange intermixed open-field holdings in

order to facilitate improved husbandry. The preamble of the second act sets

out that since 1593 [and the partial repeal of the tillage acts then] 'there

have growen many more Depopulacions by turning Tillage into Pasture', and

the first act orders that decayed houses were to be re-erected, and lands

reconverted to tillage under a penalty of 20s. per acre per annum. The second

act relates to twenty- three counties only, generally those of the Midlands,

with one or two southern counties, and Pembrokeshire in South Wales. These

were the last of the depopulation and tillage acts, and they escaped the

general repeal of such acts in 1624, and remained in force (in theory) until

1863.

The Policy of the Early Stuart Governments

Probably in Stuart times baser motives weighed more heavily with the governmental

authorities. The Stuart policies, especially that of Charles I, were as Tawney

says, 'smeared with the trail of finance'. Enclosure, at any rate enclosure

leading to depopulation, was an offence against the common law. Commissions

inquired into it, and in many cases the statesmen and divines who composed

these were inspired by the loftiest motives. The general action of the

government, however, was to use the Privy Council and the courts, especially

the prerogative courts, the Court of Requests and the Star Chamber, the Councils

of Wales and the North, as means of extortion. The offenders were 'compounded

with', i.e. huge fines were levied so that the culprits might continue their

malpractices.

In 1601 a proposal to repeal the depopulation acts was crushed upon the ground

that the majority of the militia levies were ploughmen. In 1603 the Council

of the Nortt were ordered to check the 'wrongful taking in of commons and

the consequent 'decay of houses of husbandry. . .'. From about 1607 to 1636,

the Government pursued an active anti-enclosure policy. In 1607 the agrarian

changes in the Midland had produced an armed revolt of the peasantry, beginning

ii Northamptonshire, where there had been stirrings of unrest at any rate

since 1604. The counties mainly affected were Northamptonshire, Bedfordshire,

Buckinghamshire, Huntingdonshire, Leicestershire, the three divisions of

Lincolnshire, and Warwickshire. The leader was a certain John Reynolds, nick

named Captain Pouch, 'because of a great leather pouch which he wore by his

side, in which purse he affirmed to his company there was sufficient matter

to defend them against all comers, but afterwards when he was apprehended,

his Pouch was searched, and therein was only a peece of greene cheese'. John

was soon dealt with after a skirmish at Newton, where a body of mounted gentlemen

with their servants dispersed a body of a thousand rebels, killing some forty

or fifty of the poorly-armed rustics. Some of his followers were hanged and

quartered. Promises of redress made by various proclamations were fulfilled

only to the extent of the appointment of still another royal commission to

inquire into agrarian grievances in the counties named. After it had made

its return, however, it was discovered that on legal technicalities the

commission was invalid, and little action seems to have been taken upon its

laboriously compiled returns. The local gentry were soon busily at work again

in enclosing their own land and that of others, though in 1620 Sir Edward

Coke, the greatest of English judges, who had already shown himself a keen

opponent of enclosure, declared depopulation to be against the laws of the

realm, asserting that the encloser who kept a shepherd and his dog in the

place of a flourishing village community was hateful to God and man.

A reaction set in when in 1619 there were good harvests, and the Privy Council

was concerned to relieve farmers and landlords who were suffering through

the low price of corn. This is why commissions were appointed to grant pardons

for breaches of the depopulation acts, and why in 1624 all save the two acts

of 1597 were repealed. The county justices still, however, attempted to check

the change, and in this received more or less spasmodic pressure from the

Council. In the 1630's corn prices rose again, and in 1630 the justices of

five Midland counties were ordered to remove all enclosures made in the last

two years. In 1632, 1635, and 1636 more commissions were appointed, and the

justices of assize were instructed to enforce the tillage acts. In 1633 they

were cited before the Board to give an account of their proceedings. From

1635-8 enclosure com-positions were levied in thirteen counties, some six

hundred persons in all being fined, and the total fines levied amounting

to almost £50,000. Enclosers were being prosecuted in the Star Chamber

as late as 1639. However, the Star Chamber was to vanish in 1641, and the

Stuart administrative policy disappeared with the engines by which it had

been-somewhat ineffectively and spasmodically - put in force.

If the reign in its social and agrarian policy may be judged solely from

the number of anti-enclosure commissions set up, then undoubtedly King Charles

I is the one English monarch of outstanding importance as an agrarian reformer.

How far his policy was due to genuine disinterested love of the poor, and

how far it followed from the more sordid motive of a desire to extort fines

from offenders, it is difficult to say. But even the most unsympathetic critic

must allow a good deal of honest benevolence to his minister Laud, Archbishop

of Canterbury, and some measure of it to his master. On the whole it is perhaps

not too much to say that for a short time after the commissions issued in

1632, 1635, and 1636, Star Chamber dealt fairly effectively with offenders.

The lack of ultimate success of this last governmental attempt to stem the

tide of enclosure was due, no doubt, partly to the mixture of motives on

the part of its proponents. Still more its failure is to be attributed to

the fact that again the local administrators, upon whom the Crown depended

to implement its policy, were of the very [landed] class which included the

worst offenders. A (practising) poacher does not make a very good gamekeeper!

The Commonwealth

During the Commonwealth there was little legal or admin-istrative attempt

to check enclosure of open fields. It is not clear how far this was taking

place, though there was great activity in the enclosure and drainage of

commonable waste. Some of the Major-Generals, especially Edward Whalley,

held strong views upon agrarian matters, and attempted to use their very

extensive powers to carry their ideals into operation. Petitions were prepared

and presented, a committee of the Council of State was appointed and numerous

pamphlets were written.

In 1653 the mayor and aldermen of Leicester complained of local enclosures

and sent a petition to London, very sensibly choosing their neighbour, John

Moore, as its bearer. Appar-ently it was because of this that the same year

the Committee for the Poor were ordered 'to consider of the business where

Enclosures have been made'. The question arose again in 1656 when Whalley,

the Major-General in charge of the Midlands, set on foot local inquiries,

and took fairly drastic action in response to petitions adopted by the grand

juries in his area. He hoped that as a result of his action 'God will not

be pro-voked, the poor not wronged, depopulation prevented, and the State

not dampnified'. The same year he brought in a Bill 'touching the dividing

of commons', but it failed through the opposition of William Lenthall, the

Master of the Rolls, and indeed was not even given a second reading. This

was the last bill to regulate enclosure. Ten years later, in 1666, another

bill was read in the Lords, to confirm all enclosures made by court decree

in the preceding sixty years. It also was -unsuccessful, but the fact that

it was introduced is indicative of a great change in the general attitude

towards enclosure displayed by those in authority.

Extent of Charles' penalties on inclosers

1) Introduction of tillage acts

2) Introduction of depopulation acts

3) A total of 600 individual fines on enclosing landowners as follows

[from p. 167, Gonner, E.C.K., 'Common Land and Inclosure', 1912]:

King Charles I - fines on enclosing landowners - (££)

| Year -> |

1635 |

1636 |

1637 |

1638 |

Total 1635-8 |

| Lincolnshire |

3,130 |

8,023 |

4,990 |

2,703 |

18,846 |

| Leicestershire |

1,700 |

3,560 |

4,080 |

85 |

9,425 |

| Northamptonshire |

3,200 |

2,340 |

2,875 |

263 |

8,678 |

| Huntingdonshire |

|

680 |

1,837 |

230 |

2,747 |

| Rutland |

|

150 |

1,000 |

|

1,150 |

| Nottinghamshire |

|

|

2,010 |

78 |

2,088 |

| Hertfordshire |

|

2,000 |

|

|

2,000 |

| Gloucestershire |

|

|

|

50 |

50 |

| Cambridgeshire |

|

|

170 |

340 |

510 |

| Oxfordshire |

|

|

580 |

153 |

733 |

| Bedfordshire |

|

|

|

412 |

412 |

| Buckinghamshire |

|

|

|

71 |

71 |

| Kent |

|

|

|

100 |

100 |

| Grand Total |

|

|

|

|

£46,810 |

If anyone has the equivalent amount in today's money please

contact me here and I

will include it on this page

Extract 3 - Common Land and Inclosure

By E. C. K. Gonner

Brunner Professor of Economic Science in the University of Liverpool

Macmillan and Co., Limited. St. Martin's Street, London. 1912

Extracted using a scanner so there may be minor errors. Please note the use

of the spelling "inclosure" as compared to the more common "enclosure".

'Cope writes of "the poor who, being driven out of their habitations, are

forced into the great towns, where, being very burdensome, they shut their

doors against them, suffering them to die in the streets and highways,"'

II - INCLOSURE DURING THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

THOUGH the view which regards inclosure of common and common right land as

taking place mainly at two epochs, in the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries

respectively, and as due to causes peculiar to these particular times, is

certainly less firmly held than was formerly the case, it is nevertheless

not yet realised that thus stated it gives an almost entirely false presentation

of what occurred. No doubt it is true that particular circumstances or

combinations of circumstances at certain times accelerated the movement or

invested it with some special character, but inclosure was continuous, and

a very considerable mass of evidence as to its reality and extent exists,

spread over the long intervening period of a century and a half. Some part

of this evidence has been indicated by different writers, and particularly

by Professor Gay and Miss Leonard, but as yet its mass and continuity, and

so the extent of the progress to which it testifies, have not been fully

stated. When that is done it will be seen not so much that the earlier view

was inadequate as that it was actually the very reverse of the true state

of the case, that inclosure continued steadily throughout the seventeenth

century, and that the inclosures of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

were no new phenomena but the natural completion of a great continuous movement.

In dealing with this movement throughout the seventeenth century attention

must be directed to certain matters besides continuity and extent. The districts,

the character, and the mode of inclosure require to be dealt with.

If we turn to the later years of the sixteenth century the frequent statutes

dealing with tillage and houses of husbandry afford considerable evidence

of the efforts of the government to secure adequate attention to arable

cultivation, and to prevent land suited to corn being used for pasturage.

To some extent these acts were directed to remedy conversions to pasture

which had taken place in earlier years, and, taken by themselves, they do

not, despite their stringency and frequent re-enactment, prove much more

than the difficulty of reversing by state action a movement which, whatever

its consequences, had at its base great economic causes. But this would be

a very imperfect view of the condition which prevailed at the time. Economic

causes were still at work, and inclosure was the natural response. No doubt

they were somewhat changed in character. Even if the demand for pasture was

still effective, the increased population, with its growing need of corn,

and the new possibilities of improved methods of cultivation added new reasons

for inclosure, though obviously for inclosure with different results, against

which the old reproaches of depopulation and the diminution of the food supply

could not be alleged. In respect of this tendency the evidence of writers

like Tusser and FitzHerbert seems conclusive, and it is probable that it

was due to a like perception that, despite the very obvious anxiety about

inclosure, the statute was enacted which so specifically repeated the power

of approvement enacted in the Statute of Merton.

That inclosure from which such detrimental results as those mentioned above

might be and were apprehended was, however, steadily progressing is obvious

from circumstances attending the later statutes of tillage, as from other

evidence. The words of the statutes are very significant. Thus the preamble

to 39 Eliz. c. 2 runs:-

"Whereas from the XXVII year of King Henry the Eighth of famous memory until

the five-and-thirtieth year of her majesty's most happy reign there was always

in force some law which did ordain a conversion and continuance of a certain

quantity and proportion of land in tillage not to be altered; and that in

the last parliament held in the said five-and-thirtieth year of her majesty's

reign, partly by reason of the great plenty and cheapness of grain at that

time within this realm, and partly by reason of the imperfection and obscurity

of the law made in that case, the same was discontinued, since which time

there have grown many more depopulations by turning tillage into pasture

than at any time for the like number of years heretofore."

Like language is to be found in 39 Eliz. c. I, which states, "where of late

years more than in time past there have sundry towns, parishes, and houses

of husbandry been destroyed and become desolate." A like condition of things

is stated in the tract Certain Causes gathered together, wherein is shown

the Decay of England, if it may be assumed that this was written in the

later part of the century. It relates to inclosures in Oxfordshire,

Buckinghamshire, and Northamptonshire, and complains that there has been

a change for the worse since the days of Henry VII.

Additional light on the time and on the aims of Elizabeth's ministers is

thrown by a letter from Sir Anthony Cope to Lord Burleigh concerning the

framing of the new bill against the ill effects of depopulation, written

with the draft of the bill before him. In this criticism the writer says,

"Where every house is to be allotted twenty acres within two miles of the

town I dislike the limitation of the place, fearing the poor man shall be

cast into the most barren and fruitless coyle, and that so remote as altogether

unnecessary for the present necessities of the husband mane's trade." He

then proceeds with other grounds of objection, very pertinent to the working

of the act, and important as showing the difficulties obviously experienced

in certain places. The 'very definiteness of statement is sufficient to show

that inclosures were taking place, and that they were attended in some places

at least with bad results. He specifically urges that recent titles ought

not to hinder the immediate application of the statute.

The foregoing evidence, which bears directly on the conversion to pasture

and the existence of inclosure at the time, and also on the remedy of the

former by law, can be supplemented by that of the writer of 1607, whose careful

comparison of inclosed and open lands, especially as illustrated by the counties

of Somerset and Northampton, has often been quoted. He deals not only with

the two systems but with the remedy for inclosing when that results in

depopulation. Here he considers the expediency of offering a remedy at a

time when, as he says, the mere offer or attempt may serve as an encouragement

to violent attempts at redress. Inclosure, he writes, was made the pretended

cause for the late tumults. However he over rules this scruple and suggests

that, so far as in closure is harmful, which in general he may be taken as

denying or doubting, action must be taken not only with regard to that which

has been but also in prevention of that to come. To prevent or to stay harmful

inclosure he recommends that existing laws should be maintained and that

new measures should be taken against ingrossing of lands. Briefly stated,

no one is to hold more than one-fourth of the land -of any manor, the remaining

three-fourths to remain in tenantries none of which is to exceed one hundred

acres. Side by side with this as testimony to the real existence of the movement

is the inquisition of 1607.

Though it is not intended to deal at this point with the nature of the

inclosures, it should be added that further testimony as to inclosure of

wastes is afforded by a memorial addressed in 1576 to Lord Burleigh by Alderman

Box. This memorial is interesting by reason of the information it gives as

to the condition of the land, and its general breadth of treatment. The writer

urges the necessity of increasing the tillage lands, a necessity arising

from, firstly, the large amount of good and fruitful land "lying waste and

overgrown with bushes, brambles, ling, heath, furze, and such other weeds";

secondly, the amount converted from arable to pasture, which he states has

been estimated at one-fourth of that at one time agreeable to maintain the

plough. That there has been decay of arable is assumed, and equally he has

no doubt in stating that laws made in redress have been inefficacious. The

decay and putting down of ploughs have not been stayed, "but are rather

increased, and nothing amended." His own remedy is to leave the land in pasture

alone and devote all efforts to the cultivation of the wastes. But here he

points out a difficulty, which evidently was a real one. While the wastes

existed the herbage and other profits belonged to the tenants; when divided

and. separated their division was at the lord's pleasure. Hence he advocates

the introduction, of a regular system of inclosure of wastes, the lord of

the manor, together with four or five of the gravest tenants, appointed and

chosen by their fellows, to be empowered to proceed to a division and allotment,

each allotment to be according to the rent paid and to be granted on condition

of clearing and cultivating in two years. His object was not only to supply

the lack of tillage land but to prevent division taking place under conditions

which placed the land at the pleasure of the lord; it became his and the

tenant lost the free profit which he formerly possessed in herbage, etc.

Here, however, the memorial is instanced as evidence that inclosure of waste

to the lord's advantage was taking place, at any rate to some extent. Of

course the writer's recommendation; had it been enforced by law, would have

increased the amount inclosed, though it would have removed or modified the

objection felt by the tenants and people in general and evinced in the discords

referred to, as also later at the time of the Diggers.

On turning to what occurred during the seventeenth century it will be convenient

to examine the evidence as it presents itself under three headings-general

references in tracts, pamphlets, and the like, official records, and lastly

the evidence afforded by comparisons between the state of the country in

the sixteenth and towards the end of the seventeenth century. So far as the

first two bodies of evidence are concerned the century may be divided into

periods of twenty-five years. One thing, however, must be remembered. Literary

references frequently are to movements which have been in progress for some

little time and have grown to sufficient dimensions to impress themselves

as a general grievance in a district and within the knowledge of the writer,

and yet not so long-standing as to have lost their aggressive character.

A tract on inclosure does not merely deal with the events of the last year

or so, but covers a much wider range.

So far as the first quarter of the century is concerned reference has already

been made to the analysis of the relative advantages of inclosure and open

which distinctly favours inclosure as conducing to (1) security from foreign

invasion and domestic commotion, (2) increase of wealth and population, (3)

better cultivation through land being put to its best use. In the

Geographical Description of England and Wales (1615) complaint is

made in respect of Northamptonshire that "the simple and gentle sheep, of

all creatures the most harmless, are now become so ravenous that they begin

to devour men, waste fields, and depopulate houses, if not whole townships,

as one hath written." The passage is of course copied from the Utopia.

The Commons' Complaint (1612) and New Directions of Experience to

the Commons' Complaint (1613), both by Arthur Standish, advocate inclosure

in every county of the kingdom. In the preface to the earlier tract he refers

to "a grievance of late taken only for the dearth of corn in Warwickshire,

Northamptonshire, and other places." Since this as well as the other tract

is largely a defence, or rather advocacy, of inclosing there can be no doubt

that the suggested cause was the in closing. Of Cornwall Carew writes in

1602," They fall everywhere from commons to inclosure." Again, Trigge in

The Humble Petition of Two Sisters (1604) condemns inclosure.

In the second quarter the literary treatment of the subject is not very full.

Depopulation Arraigned (1636), by R. P. (Powell), of Wells, was occasioned

by the issue of the royal commission to inquire into inclosures, and deals

in a hostile spirit with the subject. The author specially condemns what

he describes as "a growing evil of late years "-namely, grazing butchers

taking up land,-and gives some details of inclosure accompanied by depopulation.

In the third quarter and at the very beginning there is much more to be referred

to under this heading. Inclosure Thrown Open; or, Depopulation Depopulated,

by H. Halhead (1650), is a vigorous attack on those desirous of inclosing,

who are accused of resorting to any means to secure their object. As to the

district referred to, the authorship of the preface by Joshua Sprigge, of

Banbury, affords some slender ground for the conjecture that it refers to

the South Midlands. That the Midlands formed a conspicuous area is clearly

shown by other writings. In these a definite controversy centres round the

in closures of Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, and the adjacent Midlands,

while it comprises also references to other parts of the country. The first

publication in this series was The Crying Sin of England of not Caring

for the Poor, wherein Inclosure, viz. such as doth Unpeople Towns and Uncorn

Fields, is Arraigned, Convicted, and Condemned by the Word of God, by

John Moore, minister of Knaptoft, in Leicestershire (1653). To this there

appeared an answer, Considerations Concerning Common Fields and Inclosures

(1653). Moore replied in a printed sheet which apparently is lost. To

this the author of the Considerations published a Rejoinder,

written in 1653, but not printed till 1656. In this latter year Joseph

Lee, the minister of Cotesbatch, published A Vindication of Regulated

Inclosure. A final retort to both the foregoing by Moore in A Scripture

Word against Inclosure (1656) concludes the controversy. By its side

must be placed The Society of the Saints and The Christian Conflict,

both by Joseph Bentham, of Kettering. With regard to all these some few

points require notice. The controversy begins with the inclosures in

Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, and the counties adjacent, and then extends

somewhat to other inland counties in general, one writer alluding to the

inland counties" where inclosure is now so much inveighed against." References

in particular are made to inclosure in Warwickshire, and to the existence

of in closed districts in Essex, Kent, Herefordshire, Devon, Shropshire,

Worcestershire, and even Cornwall, though it cannot be concluded that the

allusion is to recent inclosures in these latter counties. In the second

place even Moore is careful to distinguish between inclosure which depopulates

and that which has no such effect. When hard pushed he goes further, writing,

" I complain not of inclosure in Kent or Essex, where they have other callings

and trades to maintain their country by, or of places near the sea or city."

Thirdly, a very important consideration as to the ultimate effect of the

movement is raised by those in its favour in the assertion that very often

in closure is laid to pasture and then after a rest returned to arable use

greatly enriched. This assertion is accompanied by a consider able number

of instances. Probably the references to the large inclosures in North Wiltshire

by John Aubrey in the Natural History of Wiltshire were written during

this period, for his studies began in 1656, though his preface was not written

until 1685. The same period saw the publication of what was one of the most

important seventeenth century works dealing with the subject, Blith's

English Improver (1652). In 1664 Forster in England's Happiness

Increased prognosticates a rise in the price of corn from inclosure which

he deplores, stating, " more and more land inclosed every year."

During the last quarter of the century we have the many definite assertions

by Houghton in his valuable Collections. In 1681 he writes of the

many inclosures which" have of late been made, and that people daily are

on gog on making, and the more, I dare say, would follow would they that

are concerned and understand it daily persuade their neighbours." He instances

the sands of Norfolk as an example of what they may effect and urges the

need of a bill of in closure. In 1692, in arguing against the common notion

that inclosure always leads to grass, he adduces instances to the contrary

from Surrey, Middlesex, and Hertfordshire. In 1693 he gives some account

of inclosed land in Staffordshire, and adds, " I cannot but admire that people

should be so backward to in close, which would be more worth to us than the

mines of Potosi to the king of Spain." In 1700 he argues again in favour

of a general act which should be permissive. Equally significant testimony

is borne in 1698 by The Law of Commons and Commoners, which devotes

a special section to the matter of legal inclosure. Campania Felix, by

Timothy Nourse (1700), deals with the advantages of inclosure, as also does

Worledge in the Systema Agriculturae (third edition, 1681). General

references of this kind during the latter part of this century multiply as

literature dealing with agricultural systems increases.

But to illustrate the condition of things during the last quarter of the

seventeenth century, or even during the latter half, we must turn also to

books and tracts published shortly after its termination. In The Whole

Art of Husbandry; or, the Way of Managing and Improving of Land, by J.

M., F.R.S. (John Mortimer), published in 1707, inclosure is treated as obviously

beneficial, as with reference to it the writer adds, " I shall only propose

two things that are matters of fact, that, I think, are sufficient to prove

the advantages of inclosure, which is, first, the great quantities of ground

daily in closed, and, secondly, the increase of rent that is everywhere made

by those who do inclose their lands." Again, the editor of Tusser in Tusser

Redivivus (1710), commenting on a reference by Tusser, says, "In our

author's time inclosures were not as frequent as now." John Lawrence in A

New System of Agriculture (1726) contrasts the inclosed and open fields

in Staffordshire and Northamptonshire to the advantage of the former, and

says as to the north that the example of Durham, the richest agricultural

county, where nine parts in ten are already inclosed, is being followed by

the more northern parts. He expresses surprise that so much of the kingdom

is still open. Edward Lawrence in The Duty of a Steward to his Lord

(1727) gives a form of agreement which he recommends to proprietors anxious

to inclose. Equal testimony to the reality of the movement is offered by

J. Cowper in An Essay Proving that Inclosing Commons and Common Fields

is Contrary to the Interests of the Nation, in which he seeks to controvert

the opinions of the Lawrences. Writing in 1732 he says: " I have been informed

by an ancient surveyor that one third of all the land of England has been

inclosed within these eighty years." Within his own experience of thirty

years he has seen about twenty lordships or parishes in closed. An Old

Almanac, which was written and printed in 1710, though it has a postscript

bearing date 1734, urges the need of a general act and expresses the opinion

that the consent of the lord with two-thirds of the tenants should bind the

minority in any inclosure. Again, in the Dictionarium Urbanicum (1704)

we read of "the great quantities of lands which in our own time have laid

open, in common and of little value, yet when in closed . . . have proved

excellent good," etc.

Turning from this kind of evidence to that of an official and legal character,

it is fortunate that the comparative weakness of the testimony of tracts

and pamphlets during the first half-century can be otherwise strengthened.

The inquisition into inclosures in 1607 refers obviously to what had taken

place in the latter period of the preceding century, but during the reigns

of the first two Stuarts the anxiety as to depopulation and scarcity which

are apprehended as a probable if not a necessary result displays itself in

almost undiminished force, as it may be seen from the Register of the Privy

Council. In the reign of James I. there are some few references to cases

of inclosure, the most interesting of which deals with the case of Wickham

and Colthorpe, in Oxfordshire, in respect of which a bill in chancery for

inclosure had been exhibited by Sir Thomas Chamberlain. Lord Say, however,

had pulled the hedges down with considerable disturbance, and thus the matter

came to the attention of the council. In a letter to the lord-lieutenant

from the council it was pointed out that, owing to Lord Say's action being

known, "there is very great doubt, as we are informed, of further mischief

in that kind, the general speech being in the country that now Lord Say had

begun to dig and level down hedges and ditches on behalf of commons there

would be more down shortly, forasmuch as it is very expedient that all due

care be taken for the preventing of any further disorder of this kind, which,

as your lordship knoweth by that which happened heretofore in the county

of Northampton and is yet fresh in memory, may easily spread itself into

mischief and inconvenience." There are, however, but isolated instances of

intervention.

More systematic attention to inclosure is shown during the second quarter

of the century. The great administrative activity of the council in the fourth

decade found a sphere here. On 26th November, 1630, a letter was directed

to be sent to the sheriffs and justices of the peace for the counties of

Derby, Huntingdon, Nottingham, Leicester, and Northampton, calling for an

account of inclosure or conversion during the past two years or at that time

in progress. In the replies from Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire many

great inclosures were reported, and directions were accordingly despatched

as to the course to be taken; some, as tending to depopulation or the undue

diminution of arable, were to be thrown open. That this was deemed unnecessary

in other cases is evident from a subsequent letter of 25th May, 1631, whereby

inclosures begun might proceed on due undertakings that the houses of husbandry

be not restricted injuriously or the highways interfered with. That considerable

care was exercised in the matter is evident from further references in the

proceedings of the council. On 9th October, 1633, the judges of assize were

ordered to attend the board on the 18th to give an account of their doings

and proceedings in the matter of inclosures. Unfortunately in the account

of the meeting on this date and of the interview with the judges no definite

reference is made in the Register to what transpired in the case of inclosures.

In general it is said that the justices of the peace do not meet often enough

to carry out the Book of Orders and that the returns of the sheriffs are

defective. Among the State Papers is a copy of a warrant to the attorney-general

to prepare commissions touching depopulation and conversion of arable in

the counties of Lincoln, Leicester, Northampton, Somerset, Wilts, and Gloucester.

While it is doubtful if much was done directly to stay inclosure, and while

with the approach of the Civil War the time of the council was necessarily

devoted to other matters, the existence of an inclosure movement is certain.

It is equally clear that information was obtained of which some use was made,

though possibly for other ends than the benefit of the agricultural interest

and the people. In 1633-4 we find a proposal that all inclosures made since

16 James I. should be thrown back into arable on pain of forfeiture, save

such as be compounded for. The suggestion was not lost sight of, and from

1635 to 1638 compositions were levied in respect of depopulations in several

counties of which an account is fortunately preserved. Some 600 persons were

fined during this period, the amounts in some cases being considerable. The

following is a summary of the sums obtained from compositions in the several

counties affected during these years:

|

County |

1635

£ |

1636

£ |

1637

£ |

1638

£ |

Total

£ |

|

Lincolnshire |

3,130 |

8,023 |

4,990 |

2,703 |

18,846 |

|

Leicestershire |

1,700 |

3,560 |

4,080 |

85 |

9,425 |

|

Northamptonshire |

3,200 |

2,340 |

2,875 |

263 |

8,678 |

|

Huntingdonshire |

|

680 |

1,837 |

230 |

2,747 |

|

Rutland |

|

150 |

1,000 |

|

1,150 |

|

Nottinghamshire |

|

|

2,010 |

78 |

2,088 |

|

Hertfordshire |

|

2,000 |

|

|

2,000 |

|

Gloucestershire |

|

|

|

50 |

50 |

|

Cambridgeshire |

|

|

170 |

340 |

510 |

|

Oxfordshire |

|

|

580 |

153 |

733 |

|

Bedfordshire |

|

|

|

412 |

412 |

|

Buckinghamshire |

|

|

|

71 |

71 |

|

Kent |

|

|

|

100 |

100 |

(apologies but this table doesn't seem to have come out 100% - please see

the section immediately above this article - it will print correctly if you

download the Word document - ed.)

Having regard to the size of the counties and the number of instances in

each, this may be taken as indicating a considerable amount of inclosure

in the case of the first six counties-Lincoln, Leicester, Northampton,

Huntingdon, Rutland, and Nottingham. Only inclosures leading to depopulation

were supposed to be included.