Index | Homepage | Good Links | Bad Links | Search | Guestbook/Forum

My thesis is that it is no accident that cars have taken over from public transport on both sides of the Atlantic. There are powerul interests that want to destroy essential shared resources and massively increase our consumption of, and reliance on, oil. The social, financial and environmental costs of public transport infrastructure are tiny if compared to the total costs of maintaining a massive car stock and road infrastructure. So why is the car so prevalent. Social Engineering in my view. Read on for the evidence.

The streetcars were successfully shut down in the U.S.A. by the roads lobby. Why not here in the U.K.?

How come then, it's more expensive to travel in a multi-occupancy vehicle being used 18 hours a day than it is to use a 1 to 4 person vehicle (a car) that stays idle 95% of the time? Answer, subsidies and financial trickery. The government subsidies that favour the car are directly opposed to social and environmental concerns. Rail travel is also much safer, so why subsidise the dangerous option?

In addition there is clear evidence provided by Ken Livingstone's Fares Fair experiment, in the 1980's, that public transport tickets are deliberately overpriced in the UK. What is going on! I believe powerful commercial interests made sure in the early sixties that commercial freight, both by road and rail, would be heavily subsidised by the private traveller.

The American Association of State Highway Officials ran road surface damage tests costing $27million in the 1950's which showed the damage caused to a road surface by a given vehicle axle was proportional to the weight of the axle to the power of four.

In other words, where it might be assumed that the wheels of a heavy lorry carrying 10 tons would cause ten times as much damage as the wheels of a lighter vehicle bearing a ton, the actual figure was a thousand times greater. For example; a 12-ton lorry with two axles was causing as much damage as 160,000 cars.

A German survey in the early 1980's revealed that freight vehicles might be paying no more than 12.5 per cent of their true cost.

![]()

1. Railways

1. Railways

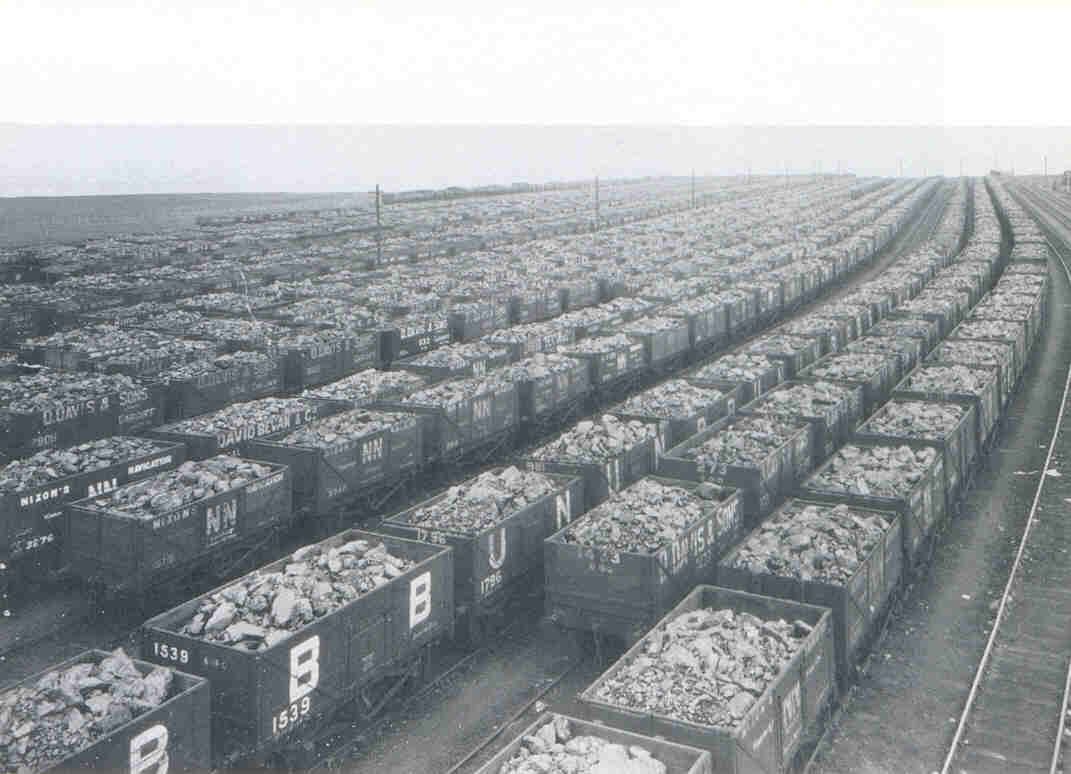

Welsh Steam Coal wagons at Cardiff Docks in 1927

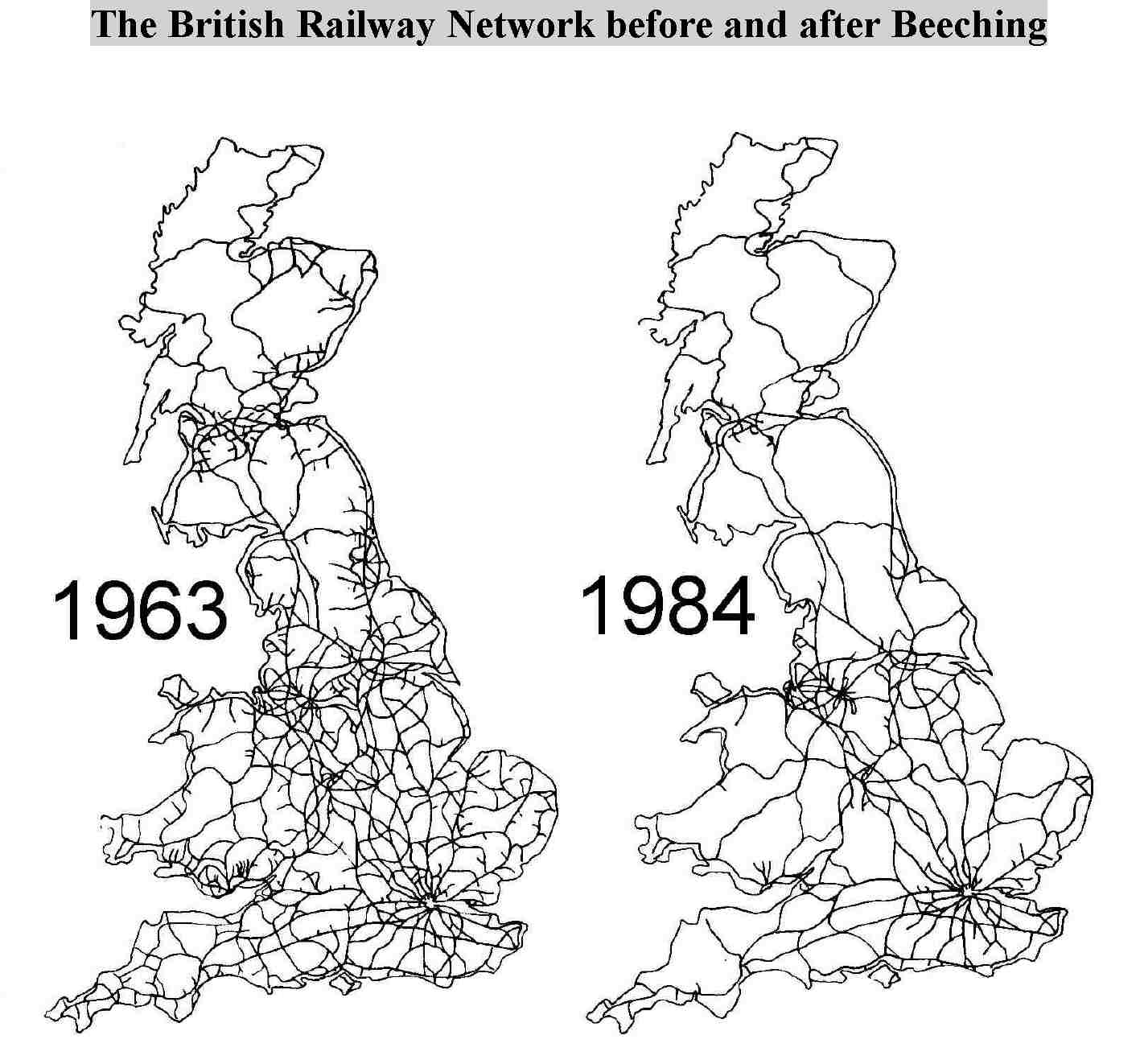

The first place to look is the reports that led to Dr. Beechings railway destruction plan, known at the time as the 'Re-shaping Plan'. This plan was an essential 'justification' for Britain's motorway building programme begun in the early sixties.

Did Beeching himself write it? Not exactly. It was prepared by a ministry of Transport advisory group of industrialists, including Beeching, called the Stedeford Committee [see below] who were appointed by Tory transport minister Ernest Marples. Marples was a director of Marples Ridgway, the road building company that built the Chiswick flyover - and much more. The brief of the Stedeford committee was secret as was the report to the minister. Immediately suspicious. Not one of the Stedeford members had been significantly involved with transport before, all four non civil-servants were industrialists¹. Dr. Beeching was straight from the board of I.C.I.. The committee begins to look like a fix by the industrial elite.

I have heard and read how the government, through the Department of Transport, pay the vast sums needed for road infrastructure. So, one might expect, in the interests of a competive transport market, they would pay for rail infrastructure too. But government insists rail infrastructure is paid for by the rail fares, hardly a level playing field! When the railways stop returning a profit, the fact that the transport market is regulated in favour of the car is ignored and there is deep indignation that railways are not returning a profit. The massive overuse of oil that cars bring must be making someone, somewhere, an obscene amount of money. I begin to smell a honking great rat!

Let's not forget another very good political

reason for interfering in the 'free market' in transport, the powerful rail

unions ASLEF and the NUR. Once these unions had the power to bring British

industry to its knees, just as they did between 30th May and 14th June 1955.

This strike occured immediately before the changeover from public to

private transport. You can't unionise a car, the railway abandonment served

to break transport union power once and for all.

Let's not forget another very good political

reason for interfering in the 'free market' in transport, the powerful rail

unions ASLEF and the NUR. Once these unions had the power to bring British

industry to its knees, just as they did between 30th May and 14th June 1955.

This strike occured immediately before the changeover from public to

private transport. You can't unionise a car, the railway abandonment served

to break transport union power once and for all.

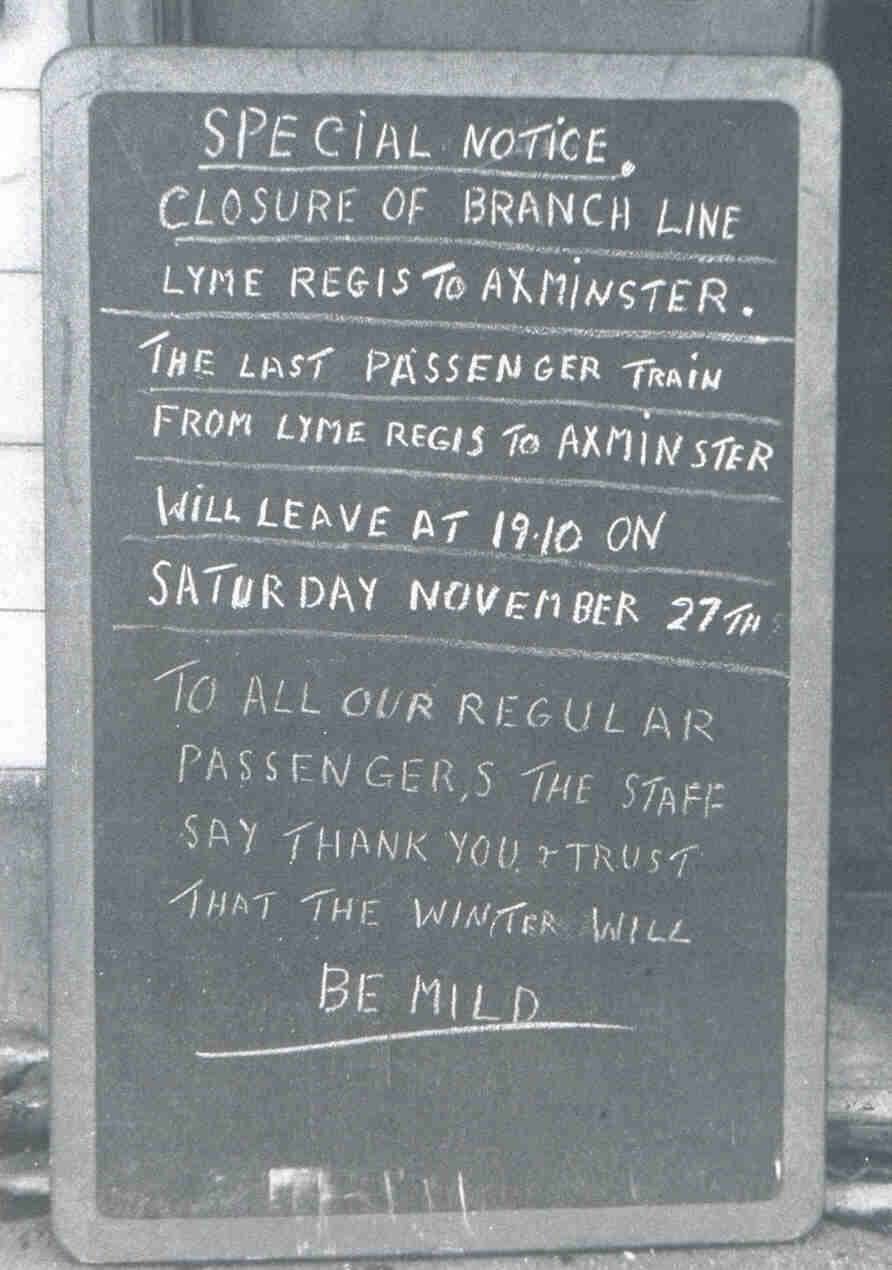

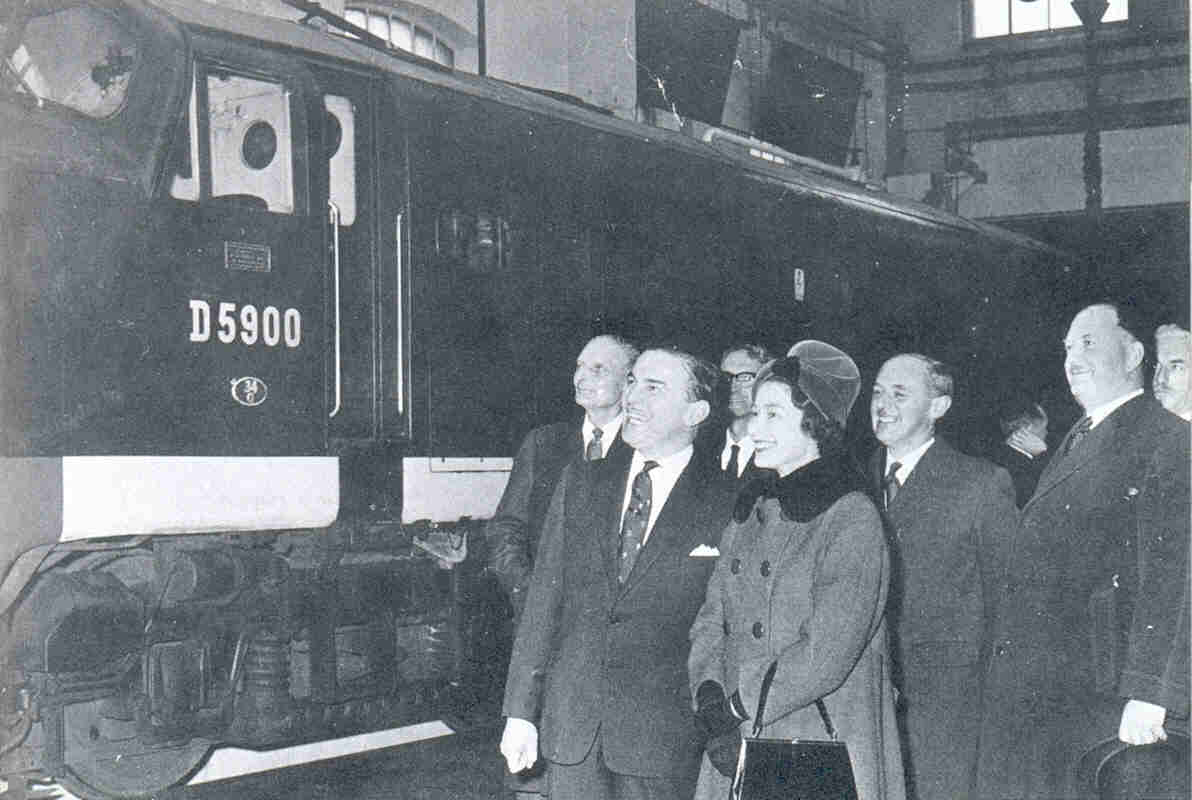

November 1965 - photo John A. M. Vaughan

With a combination of infiltration (cf. the now famous infiltration of the National Union of Mineworkers by MI5) and economic/political union busting campaigns such as happened on the railways Socialism in the UK has been brought to its knees. And many Socialist ideals have been shattered.

Lasted from 29th May to 14th June 1955. Pay differentials strike over the price of a packet of cigarettes per week, called just days after Eden's Conservative victory at a General Election. Brought British industry to a standstill after two weeks and forced a government climbdown. British Transport Commission settled pay claim.

After this UK government transport policy switched to roads.

..by sending an email with the subject "Have Your Say" - my email is here - and I will respect your anonymity if you wish.

I have been a member of those pests the Freemasons, 1987 to 1989, and ditched them. Had nothing but trouble since. Mainly oil industry career bother.

I have lost a number of jobs which I suspect had something to do with these pathetic sycophants.

Then you educated me with the Bilderberg bolshy bunch, and now I am probably the worst cynic on the planet.

The reason I write is the UK Transport topic and Beeching's Axe.

Having worked in the oil industry a fair part of my life, I have often wondered why this noble twat ripped our heritage up so fast. Politicians argued taxpayers losses. What nonsense. All industries owned by the nation, are manipulated by the bean counters to alter public opinion.

My thoughts were drawn to the timing of the discovery of North Sea oil, and Beeching's axe.

My theory was American Oil Zionists telling the UK government what will happen. i.e. You have a transport infrastructure that is far too efficient Where are you going to sell your oil? The OPEC countries are under our control and we do not want your oil upsetting our cosy world market. You will have to sell it on your home market. If you agree, we will give you the zillions of bucks to build your rigs, because you can't afford to build them, and we will assist you in sucking your oil out and polluting your fishing grounds...... BUT you must rip up your tracks and build for the road lobby. Look at the taxes you can rip the public off for........ ZZZzzzzzz.

The rest is history.

Hence, I live in France. Here life is not so hypocritical, and not so many Zionists running the shop.

Kind regards

John Xxxxxxxx

Date: Wed, June 17, 2009 2:39 am

<jimmy.1959@hotmail.co.uk>

Hi Tony,

I was looking at your Dr. Beeching report thing and although I have only read a small part of it I can fully understand it and I totally agree with the way the railways in the UK where destroyed only for transport to be shifted to the roads. I live in Springburn in Glasgow which was once known as the Locomotive builders to the world and once built a quarter of the worlds loco's. Some of the lies in the Beeching report make me sick and the moves that where made to close lines was appalling i.e. in an attempt to close the Settle and Carlisle line they changed the timing of the connecting train to Leeds from carlisle so that passengers would miss it by 10 minutes.

We had the best railway system in the world and even after WW2 if the money that the railways where owed by the government where paid in line with inflation from the 1936 railway revenues that had been agreed they would have got over twice the amount and would have been able to modernise the system, after all we could never have kept up the war effort as we did had it not been for our railways, a fact that was easily forgotten. Glasgow and the whole Strathclyde area as it was came out not to bad after the Beeching axe fell mainly because the greater Glasgow politicians where and still are i believe pro rail.

Although we never suffered as much a loss in railways as most parts of the UK most of the ex Caledonian Railway lines north of the Clyde disappeared. I grew up in a place called Possilpark which is on the boundary of Springburn and out side my living room window was the ex North British Railway works of Cowlairs, the main erecting shop was only about 35/40 yards from me and as a result I grew up loving railways. I have done a 38 page document on the history of the railways in Springburn from their beginning in 1831 until now and I am hoping to put it on a web site in the quite near future. i'm sorry for going on so much and I hope you don't mind and I look forward to hearing from you.

Cheers

James

I was just thinking about the Waverly route and its closure in 1969. The reason for its closure was given that it was more or less a duplicate of the west coast main line. That was nonsense but it was still closed anyway. Ok there were not a lot of passengers using the line but there were plenty of freight trains using it. Many of the small villages and even the towns that the route covered grew in size over the first decade of the lines closure and would no doubt have given plenty of passengers for the line. There has been talk for years of reopening the line as far south as Carlisle and this I imagine would be a good thing as it would give a rail link to the Scottish borders area most of which has no railway station or even lines within a reasonable distance and the bus services in most parts are totally inadequate.

A few years ago when I was doing research on Springburn's railway history and was stuck. For some reason or other I started to think about a time a couple of years earlier when my wife and I were in Blackpool. In Blackpool North station there was a large advert about taking a train trip to Steamtown in Carnforth. We took the train and when we got to Carnforth we found that steamtown was closed. When we went into a café I asked the waitress about why it was closed and she told me that it closed down two years previously. I was a bit disappointed about that advert in the railway station that was sending people on a trip to a place that was closed down. The thought of inspired me to write this little poem, hope you like it.

The late train spotter

I stood and waited in the rain

And hoped to a passing train

Not caring what class it be

A Black five or a Jubilee

A diesel with a sounding horn

Or a pannier tank the worse for worn

Yes I stood and waited in the rain

But it seems my waiting was in vain

For the last train passed here long ago

But I stood there and did not know

Until a passer - by came up and said

No trains will come this railway's dead

The last one ran in sixty - eight

And even that was running late

So I thanked him and went on my way

And cursed I stood there yesterday

I remember when I was 6 or 7 years old I used to watch the trains heading in and out of Glasgow Buchanan Street station around 1965/66. Buchanan Street station was opened on 1 November 1849 by the Caledonian Railway as what was meant to be a temporary affair but would remain unchanged until 1932. A large goods yard was opened beside the station on 1 January 1850 and was at the time the largest in Scotland. The termini station was also used for trains from south of the border until the CR opened Glasgow Central station on 1 August 1879. The Buchanan Street station was normally quiet with a couple of busy times each day that lasted for about an hour or so. When the station was rebuilt in 1932 it was more or less the same drab looking affair that earned it the poor man of the four Glasgow termini the only real difference from the original was the installation of platform canopies that had been taken from the then recently closed Ardrossan North station in north Ayrshire about 30 miles from Glasgow. The goods yard was closed on 6 August 1962 and the five platform station (platform 5 only being used by parcels trains) closing on 7 November 1966. Buchanan Streets claim to fame is that it was the swan song for the Gresley A4's on the Glasgow to Aberdeen 3 hour expresses. In the summer of 1961 a trial run was scheduled for the service using 60031 Golden Plover but due to a mechanical problem the test run was rescheduled and was completed successfully using 60027 Merlin on 22 February 1962. The three hour expresses started on 18 June that year. Railway enthusiasts came from far and near to watch and photograph these locos hard at work and I have memories of seeing them myself on over a half a dozen occasions.

It is rumoured that sometime in 1965 60019 Bittern whilst working this route was taken into the nearby Cowlairs works with some problem and emerged back into traffic a couple of days later with her smoke box number plate upside down reading 61009 and ran like this for at least two days before BR noticed and had the loco's plate put on the right way up (if this is true or not I do not know but I find it amusing if not interesting) the notorious NBL type 2 class 21/29 diesel electrics where used often on trains in and out of Buchanan Street. This class was infamous for breakdowns and on more than a few occasions even catching fire. I remember seeing one or two of them belching out more smoke than the A4's.

The A4's made their last run on 3 September 1966 and the station two months later and over two miles of main line and the station completely obliterated with no sign that they ever existed. Just over two miles from the station was St. Rollox MPD (also known as Balornock shed to save confusion with the nearby St. Rollox locomotive works) St. Rollox MPD was an average sized shed with about 70 locomotves which where mostly black fives and standard class 5's. Of the 842 Black fives built only four originally carried names and in the 1950' they where all allocated here. The loco's were 45 146 Ayrshire Yeomanry, 45 154 Lanarkshire Yeomanry, 45 157 The Glasgow Highlander and 45 158 Glasgow Yeomanry.

Hi Tony

On the subject of railways on your website, you state that the Stedeford Report was made public in 1961. The Stedeford Report was not available in the public domain until 1991 and then only grudingly and partially under the "Thirty Year Rule", because it clearly showed what a cock-up the government had made of the railways over the pevious thirty years or more, and how the railways had been grossly mis-managed by civil servants who did not know what they were doing. Beeching and Stedeford had frequent disagreements. Ernie Marples was hoping for a rather different sort of report, one which showed the railways in a bad light and which would enable him to push road building. He managed to stay in office a record five years to make absolutely certain that the report never surfaced. What was published was what became known as the Beeching Report which bore no relation to Stedeford's earlier report.

Incidentally Ernest Marples was the champion of, and was in fact a member of, the British Roads Federation, the organisation that was started in 1931 in response to a government plan to put all long haul freight onto rail at the ridiculously low and uneconomic rates that rail was forced to charge by law. The BRF, comprised not only the haulage industry, but bus & coach operators, motor manufacturers, oil companies, road contractors, and AA and RAC. Because of the subsequent pressure they exerted, the 1932 Transport Act only licenced freight operators but did not restrict what they could carry or the distances they could carry it. Between 1932 and 1939 BRF became very powerful then the war intervened. After the war they reformed and were the driving force that got Marples in place. During that government well over half the MPs had "jobs" in the motor, freight or associated industries. The rest, as they say, is history.

From: "Neil McFarlane" <neilmcfarlane(-at-)warmup.com>

Date: Wed, 21 Dec 2005

Hello Tony,

Here's another reason why I believe railways have been pushed way down the transport priority scale:

I drive a second hand car, albeit a nearly new Mercedes. It's a company car and I personally get taxed again on the value of the car when it was new (this has already been paid once by the first owner!). I also pay H.M. Tax Grabbers a hefty stipend from my paycheque for the pleasure of using it. The vehicle requires a windscreen sticker to prove to suspicious civil servants that the requisite annual road tax has been paid. Emissions tax for the engine size is also deducted from my wages. In order to make it work I have to put petrol into the tank which is also taxed. When the tyres wear out I pay tax on them too. As its impossible to service modern cars without the right computerised equipment tax is paid on parts and labour. After all this I can drive myself to wherever I want to go.

If I used a train, I would simply pay for my fare and go. Can you imagine what would happen if the railways were the first choice for everyone wanting to travel? All those hundreds and thousands of people getting to move about the country each day virtually untaxed?

Then compare the investment that say, the French government provides for SNCF: the equivalent of £50 per passenger per year, hence 200mph trains up and down the country. Switzerland invests something like £75 per head, hence the most efficient rail network in the world.

The British government invests the princely sum of &&.£5 per passenger per year. So that's why we're forced out of trains and into our stonkingly taxed and re-taxed cars whenever we want to go anywhere. Simple isn't it?

Keep it up the site!

Neil McFarlane

Roland Marshall

Roland Marshall

<randsmarshall@btinternet.com>

Date: Thu, June 10, 2004

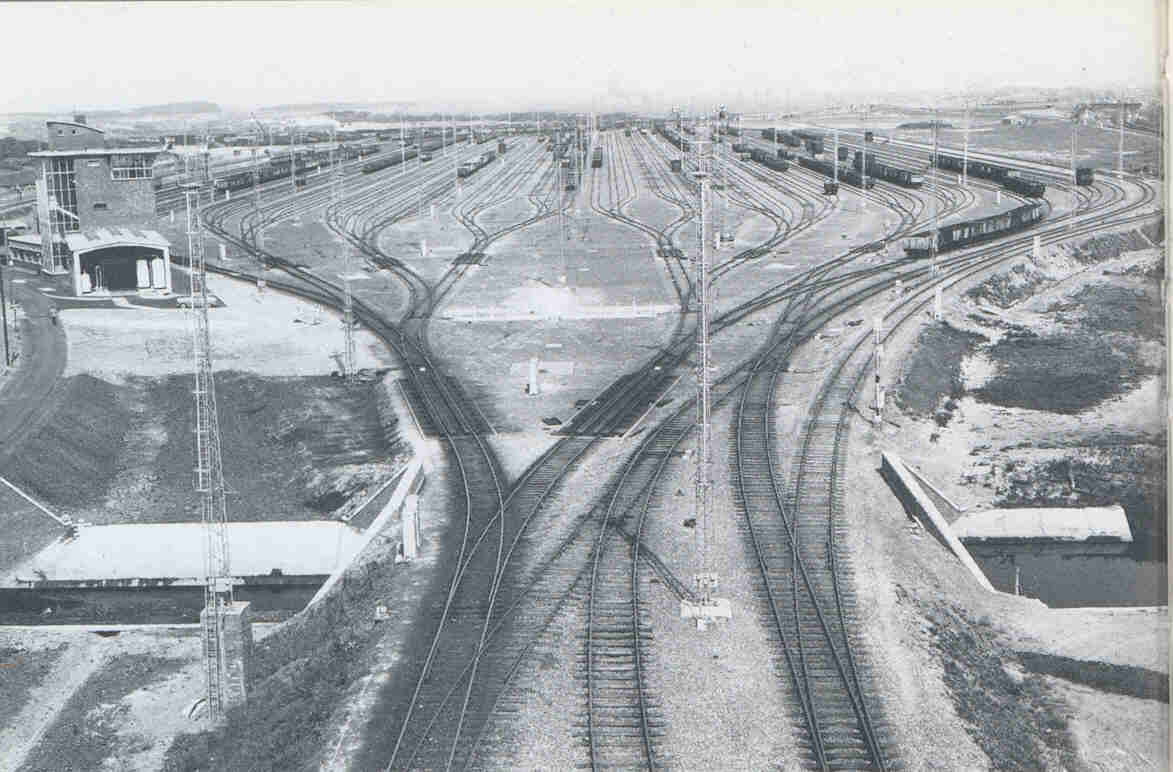

Margam Yard in Port Talbot S. Wales, opened in 1960 with 'hump' in the foreground.

A particular Beeching related story was told to me by my father which goes something like as follows;

Hungary had lost vast amounts of its rail infrastructure during the war. Much of this was plundered by the Nazis and may have been melted down for arms production or used to replace bombed tracks in Germany. Beeching was able to sell vast amounts of British "obsolete" track to them at a beneficial rate particulary with regard to junctions and crossovers that were very much in demand. Thus, what Beeching in fact had to do was close enough track in order to meet a prescribed order from Hungarian railways, and therefore the economic vs. uneconomic argument was just a convenient smokescreen. As long as he could get his hands on enough track then the deal was secure.

I can find no other evidence to corroberate this story and my father can not remember where he heard it although he says that he had no real reason to disbelieve it.

I recently was talking to a local councilor who is trying very hard to have a line re-instated and she was fascinated by this story, so I would love to find out if it has any basis in fact or is just some 60s conspiracy theory.

Many thanks for your time

Roland Marshall

Date: Tue, 18 Nov 2003

From: "bobulus" <bobulus@btopenworld.com>

Hi, Tony.

You are very brave challenging our Sociopathic Elite, but then it has to be done. The Oil Lobby have succeeded in quashing Electric railways in the NAFTA region (look at the trashing of the Mexico City-Queretaro Electrification by oil bunnies KSC and UP buying 40 diesels to trash the 39 electric locos over this route (DOH!! as Homer Simpson would say!) and have successfully poisoned UK politicians here, despite the fact this is a densely populated country. With the coming oil crash, business is going to go on as usual until one day: No more oil! The Sociopaths hold the sway and their apologists bury their heads in the sand.

Bob Battersby;

Manchester, UK.

The future development of transport in Britain

The future development of transport in Britain

Carlisle Kingmoor marshalling yards in 1963 just after it opened. Only operational for 9 years. Down Yard was made up of 10 reception roads, 37 sorting sidings and 10 departure roads. Up Yard was 8 reception, 48 sorting and 10 departure. 4 wheel wagon capacity on the Down side was 590 reception, 3,340 sorting and 730 on the departure roads. On the Up side the figures were 590, 3,340 and 730.

I just thought I would contribute my thoughts with regard to the future development of transport in this country.

I firstly believe that the only way we can truly harness the overriding potential that the railway network has is to take it back once again under public ownership. Recent events have starkly demonstrated the massive failure of the privatised railway in modern Britain.

Aside from the major accidents of recent years, we have increasing proof that these companies charged with the running of the railway have little or no aspirations for future development and expansion, unless government make good the expense incurred. In response to this beligerant attitude, I must ask the question "What is the point in paying for a project, plus the privateers profit margin when we could simply pay for the project?"

In the last day or two we have seen Network Rail take the long overdue decision to take the lines in the Reading area back under public maintainence. I sincerely hope that this is merely the start of a sweeping programme of contracts being discontinued at the review stage, and the responsibilities detailed in the contracts taken back into the public sector. The fact remains, that in order to extend or enhance the railway, we must get a real grip on the perverse cost of the most straight forward project in order to justify the money being diverted into the future of a public service- because that is what the railways are- in an age where profitability, and credibility outweigh the benefits something can give to the community in terms of deciding factors.

Furthermore, I believe that this sweeping programme of which I speak does not simply stop there. The same ethos should be rigourously applied to the joke that is franchising. Separating wheel from rail was never a good idea, that was universally recognised by everyone except those who made their fortune from it. It is these people whose hands are now stained with the blood of those who perished at Southall, Ladbroke Grove, Hatfield, and most recently of course Potters Bar. Safety is paramount, and as such should never be sacrificed at the alter of so called railway profit (there really is no such thing!) or indeed cuts to the provision the railways make, either in number of services, number of staff, or indeed the role that those staff play.

The way forward in my mind is a two fold journey; The return of the wholesale railway to public ownership, accountability and control, and a radical change in the way that this public service is administrated.

Currently we have a number of Passenger Transport Executives (PTEs) I would propose a significant increase in the number of PTEs to include the major connurbations in the country. This would complement the current PTEs, whilst providing a clear framework for the development of transport in areas where there has never before been the opportunity. These would include areas such as; - Kingston Upon Hull & East Riding of Yorkshire - Northern Scotland (Dundee, Perth, Aberdeen, Inverness) - West Country areas including Westbury, Exeter, Paignton, Plymouth - Coastway area covering Eastbourne, Lewes,Brighton & Hove, Shoreham, Worthing, Littlehampton, Barnham & Bognor Regis, Chichester. - Coastway and urban routes from Chichester to Havant, Portsmouth, Guilford, Southampton, Basingstoke, Bournemouth, Portchester and Weymouth. - Expansion of the existing PTE areas to cover routes which are outlying and/or rural, thus offeing protection to the transport needs of rural residents.

These are just a few suggested areas which could revolutionise the PTE and transport map in the future. The other big win is that these PTEs could ensure true integration between all forms of public transport because of unified control ie(Bus departures timed to coincide with train arrival times at interchanges etc)

In essence, to take the commercial element away from the railway balance sheet is to half the amount of problems currently standing in the way of numerous re-opening proposals, such as the Uckfield - Lewes line, the Hull Paragon - Sutton on Hull, Patrington, Withernsea, and the route from Hull Paragon to Hornsea to name but three, as well as numerous proposed light rail schemes, and the electrification of lines such as Oxted - Uckfield. The more cynical would say that the other half of the problems standing in the way represent the need for efficiency and value. I do believe that with the right approach, and a suitable radically pragmatic programme for the future, this could very well be achieved. Here would also be an excellent opportunity to make rail fares much more competitive, thus making rail more attractive to the would be user.

I believe that these suggestions would form the best way forward for our railways, so we can ensure that we have the level of control over railway affairs which will enable us to expand, to enhance, to sustain.

Above all this type of approach would allow us to not only take ownership of the railways, but also to turn it into something we can be rightfully proud of, the pinnacle that it once was.

Dismantling of Britain's PT infrastructure

Dismantling of Britain's PT infrastructure

Dr Beeching with Her Majesty the Queen in February 1962 on a royal visit to Stratford works. In little over a year the workshops were closed, one can't help but wonder if Beeching was buttoning his lip so as not to spoil the occasion.

From: <anglowelsh@theudderground.com> 23 Aug 2002

Dear Sir,

Your site raises many important issues, and is very interesting. The section that really caught my eye was the piece on the dismantling of Britain's PT infrastructure.

I have to agree entirely with correspondent 'JP': most of the (rural) railway system was vastly extravagent and non-viable, monuments mostly to the egos of their founders, and virtually obsolete the minute they were completed. JP also mentions the 'social revolution' that swept the country around the fifties/sixties. It's a fact of life that things progress (in the 'linear' sense of the word, at least!) and people/cultures change over time. Britain was ready for the automobile at that time, and no amount of free buses would have prevented people opting for the liberty of movement a car brings, particularly in those aformentioned rural areas.

Again, JP is absolutely spot on when he pinpoints the biggest failing of the Beeching cuts; the shoddy and spivvy selling off of the assets that once served the community and country at large. That some (if not all) of the track should have been preserved is clear, although probably not for the benefit of pasengers. No, the true worth of all this lost infrastructure is in the transport of goods and freight. How different would the UK have been had government decided to go down this route? You only have to look at the state of our 'private transport' (ie, roads) system and the environment to know the answer.

But then, it was never going to happen, was it? Because certain groups, such as the rail unions, were so 'invisibly' important to the running of industry that when they eventually sneezed, the rulers caught the flu, and the country as a whole turned on these former unsung heroes. Well, guess what? Cast your mind back a couple of years to the petrol crisis in Britain, when no tanker trucks were allowed to deliver their precious cargo. That was the farmers. Didn't we once rely on them for our food? And who did they see as unlikely allies at that time? Remember sitting for three hours on the M6, behind a 10 mile convoy of lorries?

In one way at least, the plot never varies, only the characters.

Best regards,

anglowelsh

31st August 2001

The decimation of Britain's railways in the 1960's may have been based on crooked traffic census figures. Many years ago I was talking to a former Stationmaster on the very scenic Wells-Cheddar-Yatton line, which was much used by commuters to Bristol. He told me that the most important peak-time connections at Yatton were deliberately severed prior to the taking of the traffic census. He tried to raise this fact at the public meeting before the decision was made to close the railway, but, immediately his intention became clear, his voice was drowned out from the platform. His evidence was not included in the records of the meeting. Afterwards he received oblique hints of his dismissal if he persisted in these allegations.

This is a small but personal piece of evidence.

From: David Wheldon <david@berkeleybooks.co.uk>

[Reading from your site is like breathing fresh air.]

"Transport Minister Ernest Marples"

"Transport Minister Ernest Marples"

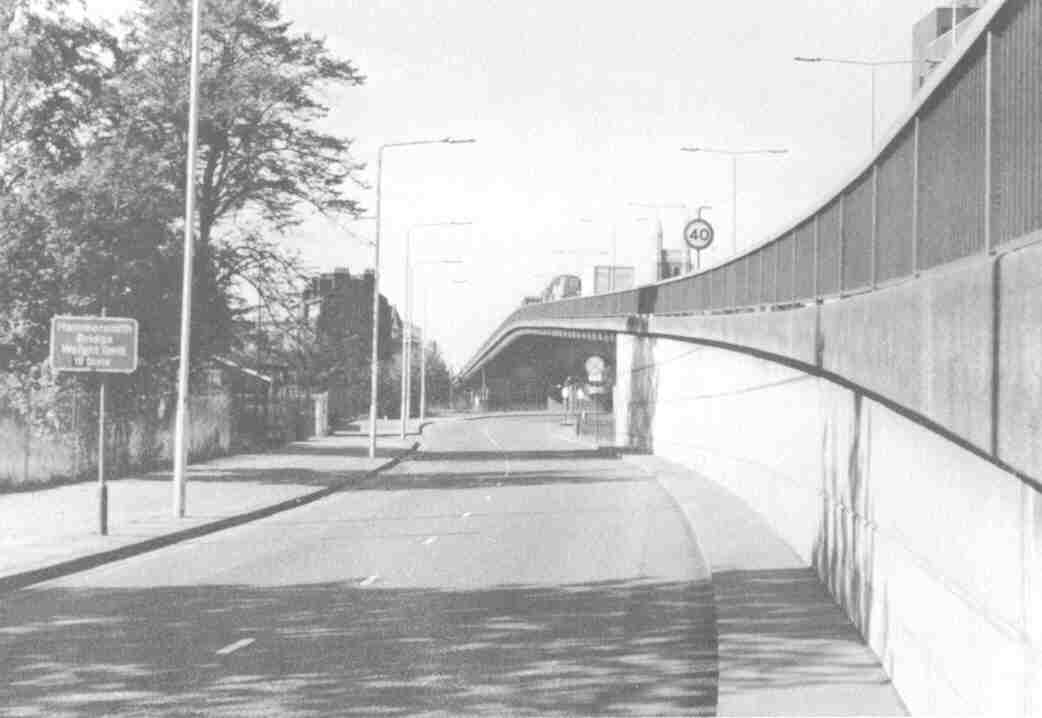

The Hammersmith Flyover built by Marples Ridgeway

Bob Griffin

Tory transport minister Ernest Marples (later 'Sir') was not just a government minister, he also owned a construction company, Marples-Ridgeway. Marples-Ridgeway's main concern was - wait for it - constructing roads. They contributed to several motorway projects during the fifties and sixties and also constructed the Hammersmith flyover in London. When it was pointed out that being transport minister as well as a road builder might be construed as a conflict of interest he (grudgingly?) agreed, and divested himself of his shares in Marples-Ridgeway - to his wife! Sleaze anyone...?

The way forward has to be the re-opening of most of the railways closed under Beeching, along with the reinstatement of the locally based distribution network. Telling the ill-informed self-interested short-termist hauliers that they could still get work driving trucks after this happens may appease them. Chucking people off former railway land to re-open has to be cheaper - both financially and in terms of the environment - than building another inch of road, yet we have to find some way to pay for it. Ultimately, this has to start with (considerable political will and) further taxes on cars and fuel. Who's first?

Thanks to Bob Griffin - for this contribution

6th April 99

"The densest network in the world"

"The densest network in the world"

John Price

Marples was a director of Marples Ridgway a road building co. that built the Chiswick flyover.

Because of the advent of cheap motor cars (The Mini) a social revolution took place that many people choose to ignore when debating this subject. What ever happened to the British Motorcyce industry, the mini ruined it not the Japanese? They did help of course.

Macmillan and co saw the railway as a victorian antiquity, a form of transport left over from a time gone by. The attitude towards the railway at that time was remarkably different from today, it is wrong to look at the railway then with the eyes of today. Today the railway is seen as the way forward in reducing grid lock on the roads. Then the railway was a leftover with quaint steam transport, unprofitable and uneconomical. Even the rail unions didnt fight the Beeching cuts.

England and Wales had been over railwayised from the start and still today it has the densest network in the world. Railway mania saw railways built that never made a penny from conception to closure. Note that of all the railways that were taken over by preservation schemes after closure, not one of them has operated a succesful public transport service, they only exist for novelty entertainment and nostalgia.

From the social point of view many many of the Beeching closures were wrong. Again social values were different in those days. remember we are talking of the days when a union could bring the country to a standstill. People equality and rights were also different in those days.

I believe the major mistake of the Beeching plan was that it allowed removal of the infrastructure. It is interesting to note that were BR did re-establish services it was only on lines were the infrastructure was intact.

There is nothing to stop railways being built again.

Public transport will never entirely replace the private car and what a god forsaken world it would be if it did.

What is needed is good goverment management of private transport.

Even if it was free there is never going to be a mass move towards public transport. [I question that!! ed.]

Rail privatisation is the best step ever towards making the railways succesful and encouraging investment but you are only going to see that on long distance peak lines and dense commuter networks. Money talks and we live in a world dictated by MONEY thats why railways were built in this country in the first place.

In case you are wondering I am a life long railway enthusiast and REALIST.

Regards JP

please note return email address captjonprice@email.com

15th November 1999

"Transport justice"

"Transport justice"

Dear Transport Minister Ernest Marples,

Ernest Marples, MP for Wallasey in the Wirral and Minister of Transport 1959-1964 in the Macmillan Government. If you read The Card by Arnold Bennett, you will meet Denry Machin. Marples and Denry had much in common.

Transport solutions in the UK have reached an cancerous unsolvable situation. The only way to resolve this situation is to dismantle the structure of obstruction piece by piece every area that stops people from using public transport. The balance of progress is measured only by positive change. It is time to grow up and stop playing with the citizens of the Great Britain.

Yours, angry and ashamed of British government,

Maurice A Willmott <maurice2000@maurice2000.screaming.net>

Tue, 21 Dec 1999

For a variety of reasons in the mid-fifties British Railways started failing to return a profit. Managers constantly complained to the government about their lack of freedom to set rates so the railways were helping pay for post-war recovery. Between 1948 and 1955 wholesale prices rose by 50% and retail prices by 34% but rail fares were forced to remain constant. Most independent observers consider this to be the single most important factor producing the defecit the railways were 're-shaped' to deal with. Both passenger and goods rates were fixed by the government in the form of the Ministry of Transport, The Railway Rates Tribunal and The Transport Tribunal¹.

The defecit was as follows²:

Table 1, Railway profitability.

| YEAR(S) | RAILWAY PROFITABILITY |

| up to 1952 | In profit |

| 1953 | Profit equalled loan interest |

| 1954 | Profit less than loan interest |

| 1955 | Break even |

| 1956 on | In defecit |

| 1960 | Defecit of £67.7 million |

| 1961 | Defecit of £86.9 million |

Chairman, Sir Ivan Stedeford [Tube Investments]

Dr R. Beeching [I.C.I.]

C. F. Keaton [JMD, Courtaulds]

H. Benson [Cooper Bros.]

D. R. Serpell [Dept of Transport]

M. Stevenson [Treasury]

Their report was made public in 1991¹. One of the many criticisms of the former British Transport Commission regime was that, of their 15 members of the BTC board, only 2 were railwaymen.

Beeching's

Bombshell, announced March 25 1963.

Beeching's

Bombshell, announced March 25 1963.

In 1961, before Beeching's 'Re-Shaping', British Rail employed a staff of 474,538.

I have found no summary detailing the extent of rail closures in the Beeching era. But a trawl of the 1963 Reshaping Plan² reveals the extent of station closures on the British mainland in the early sixties. A total of 2361 stations were closed, out of a total in 1961 of around 7,000, that's about 1/3 closed down.

The 'modernisation plan' was the British Transport Commission (British Rail's predecessor)'s response to the 'defecit' that railways were running.

Table 2: Number of railway passenger stations closed in the early sixties

| Modernisation Plan | Reshaping Plan (Beeching) | Total | |

| England | 244 | 1306 | 1550 |

| Scotland | 19 | 432 | 451 |

| Wales | 170 | 190 | 360 |

| Total | 433 | 1928 | 2361 |

[Chapter title from Allen's book³] The effect of Beeching's reshaping of the rail goods network was devastating. Before, with nearly 5,000 depots from and to which goods could be sent, the Royal Mail or the Railways covered the vast majority of the country. In practice the larger goods users, the coal shippers, cement and iron companies and, of course, the oil industry subsidised the system to bring down the handling costs of small shipments. This particular policy change meant almost all freight was forced onto the roads.

In April 1961 there were 4,995 goods depots in the UK handling 4.4 million tons a week. The total number of ton miles transported by British Railways in 1961 was 17,590 million

Table 3: The state of the rail network, track route miles in 1961²

| Freight only track miles | Mixed traffic (pass. & freight) miles | |

| 4+ tracks | 100 | 1,500 |

| 3 tracks | 100 | 400 |

| Twin track | 1,200 | 10,000 |

| Single track | 2,700 | 5,900 |

| Total | 4,100 | 17,800 |

Cost:

Maintenance of the above 17,800 route mile network, including signalling, cost £110 million/year in 1961².

The re-shaping plan closed 5,000 route miles of the above network³.

Barbara Castle was the next Labour transport minister. She found she could not change the direction her predecessor had taken the railways in.

Let's think laterally... what about... 'the other end of the tunnel'? Who would be most likely to benefit from a fix-up of national transport policy? The big rail users maybe? So that the network could be 're-shaped' to bring down their costs and stop the subsidy that was going from the bulk rail users to small customers. Then there was the oil companies, they would be eager to see consumption of petrol go through the roof with a greater reliance on the car.

The legacy is not forgotten in the corridors of power. Dr. John Marek, MP for Wrexham, spoke out in the House of Commons in 1996 against Beeching!

When the 50th anniversary of Britain’s ‘Beeching Report’ passed recently, magazines TV and radio all marked the occasion with retrospectives on the man who took a hatchet to half the 4,000-odd stations and 6,000 miles of Britain’s railways.

Back in 1963, Dr. Richard Beeching ripped the heart out of the world’s first and greatest railway network, but not one of those articles or programs mentioned that Beeching had no qualifications whatever for what was an accountant's job. His expertise was metallurgy and he'd just helped develop Britain's first atomic bomb.

Britain was the first country to industrialize and used her manufacturing muscle to become the great empire in the 19th century. It wasn’t just technology, like the invention of the steam engine, but a national policy of mass urbanization, transferring labor from agriculture to armaments and industry that put Britain ahead of the world. Mass evictions of the peasantry, known as enclosures, kept the wheels turning in the factories, William Blake’s ‘Dark Satanic Mills’ were filled with hundreds of thousands of homeless men with hungry families to house and feed, desperate for money for rent and food.

The wider empire was built on one particular invention, the railway. Moving coal, iron ore, wool and other raw materials as well as manufactured goods off the canals and uphill, down dale, cheaply and at speed gave Britain the edge as a massive shipbuilding program projected Queen Victoria’s power across the globe.

Even as Britain’s influence waned between the wars and the deliberate retreat from empire post WWII to make way for the US empire, the railways underpinned everything, moving people, goods and services, wherever they were needed and with a minimum of cost or fuss.

Across the Atlantic in the 1920s, though, people were about to be forced off the rails. Rockefellers’ Standard Oil Company teamed up with the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, Mack Truck and General Motors automobile lobby to set up a bogus public transport firm National City Lines (NCL). Streetcar (tram) companies all over the US were taken over by NCL, which deliberately failed to maintain or replace worn out vehicles.

As streetcar lines collapsed, commuters were persuaded to buy automobiles that were rolling off the new production lines. Though the Standard Oil monopoly before it had been broken up by US antitrust laws, the Rockefeller shareholding family was finding new ways to extend its influence. Part of the NCL plan was to make future governments dependent on them for fuel tax revenue.

It was Nazi Germany that brought autobahns to the world, followed by US freeways and eventually European auto-routes and motorways in the 1960s. The agenda was threefold: shift travel away from unionized public transport, increase oil consumption – and therefore fuel and vehicle tax revenue - and finally to shift power, forever, into the hands of giant private oil companies like Exxon, Shell and BP.

This was a brave new fossil fuel led world where a dependency on energy would drive economic growth like never before. Governments and people alike would have to get used to the car. Public transport was way too fuel-efficient.

‘Beeching Report’: Myth v reality

A two-week rail strike just before the 1955 general election in Britain, which some now believe was deliberately provoked for political gain, brought the country to a halt. A 'state of emergency' was declared two weeks into June and the political classes were reminded just how reliant the nation was on the whim of transport unions.

Although the oil companies hadn't made it public, North Sea Oil had also been discovered, so in order to attract US investment into the ambitious offshore drilling program there was pressure from the oil lobby behind the scenes to open up a vast new market for petrol in the UK before releasing the cash to build the rigs. The new oil stream must not be allowed to depress the world oil price and demand for the petrodollar.

With consecutive governments, particularly Tory Transport Secretary Ernest Marples - who owned road-building firm Marples Ridgeway - the industrial lobby got its way. Passenger travel on the railways would in future subsidize bulk freight transport.

Even the newly-constructed state-of-the-art freight marshaling yards such as Whitemoor in Cambridgeshire were phased out, with the railways only taking container traffic or entire train loads of coal, ore, etc. for big business. One third of the rail network and half the stations had been closed.

Who was 'Ax Man' Dr. Richard Beeching?

Retired railway manager and author Ted Gibbins explained in his ‘Blueprints For Bankruptcy’ (1995) that the government’s British Transport Commission, later the British Railways Board too, had been consistently forced to keep fares artificially low by the government. The railways had been 'regulated' into making a loss year after year, when on a looser rein they could easily have turned a profit.

Both in 1963 and five decades later in 2013, commentators mused about Beeching’s credentials for the job of ‘reshaping’ Britain’s railways. And well they might. The plan was sold to public and politicians on two myths: those railways could no longer make money and that the door-to-door technology of the motor car was simply more convenient. Few seemed to envisage the long commutes and choked roads of today.

So it was with the stage set for the revolutionary motor car which was already sweeping across the United States and Germany that, out of nowhere, Beeching stepped on to the national stage with the grim news that Britain’s railways’ days were numbered.

In ‘Doctor Who? Atomic Bomber Beeching and His War on the Railways’ (2013 eBook), former editor of the British Aircraft Corporation’s magazine and MEP Richard Cottrell was the first to expose the Ax Man’s shadowy past.

Introduced to the British public simply as chairman of Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) Beeching's link to explosives and nuclear weapons was never mentioned.

After a stint at the Woolwich Arsenal designing anti-tank weapons in World War II, Beeching had been moved on to the top secret ‘Tube Alloys’ project which was a cover for the development of the first British atomic weapons. At Royal Ordnance’s secret Fort Halstead base under the North Downs near Sevenoaks in Kent, Cottrell reveals, Beeching’s expertise in metallurgy made a key contribution to Britain’s rudimentary nuclear arsenal. The success of Britain’s 1950s atomic testing program brought Beeching the top job at ICI.

Qualifications in metallurgy and state-of-the-art explosives were not, you might think, the ideal qualification for a man whose job was to go through the accounts of British Railways with a fine toothed comb. No, the reason Beeching was hired was because the Conservative government had already decided his job was chop up the railways to make way for the motor car and they needed a figurehead that could keep his mouth shut.

With lines to be closed decided before Beeching's 'surveys' took place civil servants at the Department of Transport set about the simple but impish task of meddling with train timetables to make sure branch line trains left just before connecting trains arrived, nudging ever more passengers off the railways. Running costs of lines they wanted to close were grossly inflated, but nether rail unions nor public were allowed to see the figures to check them.

Where these fraudulent figures were exposed, as in the pamphlet ‘The Great Isle Of Wight Train Robbery’ (1969) press, public and political furor led to lines earmarked for closure being reprieved, but atomic Bomber Beeching ran a tight ship and exposures of his closure orders to scrutiny were few and far between.

A top secret de-industrialization plan was in place too. In late 1967, British Rail printed a secret 'Blue Book of Maps' with details of coalmines, steelworks etc. and associated rail lines secretly earmarked for closure over succeeding decades. Britain's devastating 1984/5 mine closure program and subsequent strike had been secretly anticipated by government and oil industry alike, decades before.

David Henshaw in his ‘Great Railway Conspiracy’ (1991) is one of the only analysts to have understood the secret Marples/Beeching axis untruth that rural rail, and urban rail outside London, could never pay its way, was simply propaganda cooked as a cover story, to take out the competition, by the oil industry and roads lobby.

Before addiction to oil & cars suffocates us all…

What hapless Britons are left with now after railway privatization in 1993 is the most expensive railway network in the world to travel on. In some places 10 times dearer than an equivalent journey in Austria, for example, a whole succession of racketeers from track and rolling stock owners to platform and turnstile operators draw their pound of flesh, from the great British public’s need to get around.

Banks and hedge funds own the rolling stock which is leased to deeply-indebted train operating companies such as First Group, which leases the bare minimum of carriages. This leaves trains jam-packed with standing-room only through large parts of the day. Even the minimum fares seem carefully pegged just above what it would cost in petrol to make a journey by car. A legacy, perhaps, of the energy industry's economic imperative, still nudging rail commuters to buy a car.

Along with electricity, gas, water, telecommunications, defense procurement, airports, the Royal Mail postal service, home care and housing, rail travel is just another government-approved scam. With commuters lining the pockets of overpaid bosses and shareholders, and exorbitant prices for what should be national utilities, turning a profit, at home or in business, becomes almost impossible.

Like energy and housing costs, travel costs by rail or car are slowly bankrupting families and small businesses alike. If policies don't change, all that will be left will be the boards of directors of the giant transnational corporations who have won the favor of what is now the ultimate power in the Western world, the banksters.

New Zealand discovered state railways work for public

Perhaps Britain's free post war socialist health service and social security miracle meant the British had it too good for too long? Perhaps because the London media is too close to the City's dark heart? Or perhaps it's just because all the main political parties have sold out? But the British public, it seems, will put up with anything. Not so in New Zealand, where privatization of the railways brought about a political storm as well as a split in the Labour party. It was re-nationalized in 2008.

Meanwhile, as the British government sinks ever deeper into the black it will be forced to consider the astounding success of Britain's only state run East Coast Main Line region which is not only top-rated in the UK for customer satisfaction but, unlike the privately run regions, has paid over a billion pounds into the treasury.

Nevertheless the government is determined to sell off the East Coast operating company two months before the general election in March 2015.

"Reprivatization of the East Coast Main Line defies all economic logic and is nothing less than an act of industrial vandalism," rail union leader Mick Cash told the Guardian in September this year.

It seems even with such a crystal clear example of the only state run railway being the best in the country the government still determined to overturn it and set up another racket with a Tory party donor in charge and hundreds of thousands of captive passengers as the victims.

It's a tough ask, but perhaps so close to a general election, and with Labour toying with the idea of rail nationalization, they, together with the commuting public could break the combined lobby of the oil industry, road lobby, media and banks? The railway racket has come to sum up everything about Britain's post 'swinging ’60s' decline, but perhaps, as in New Zealand the angry voice of commuters, squeezed in like sardines, and the cold hard economic successes of nationalization can turn things around?

Beeching's accidental stroke of genius

Bomber’s legacy, though, hasn’t been all betrayal. By accident his hatchet fell at the same time that Britain’s steam locomotives, kept on well beyond their continental networks because of Britain’s plentiful supplies of coal, were being replaced by diesels.

Those steam engines chuffed off to the overgrown lines that Beeching closed, and as a result many have been preserved. Now over 150 charitable steam railways, some of which are regular enough to be used by commuters, are dotted across the country on the old closed lines.

It is as if those heritage rail services are biding their time, waiting for the day when the policy-makers slip out of the grip of the oil lobby, regain their sanity and re-lay the old tracks. Travelers can then once again begin to pay, for the first time since the 1960s, just a little more than it costs railway operator, to get where they need to go.

Biographical information about Dr. Richard Beeching extracted

from:

Biographical information about Dr. Richard Beeching extracted

from:

'Dick' Beeching, as he was known in the family and by his closest friends and associates, was the second of four brothers and he was born in a small terraced house in Sheerness in the Isle of Sheppey in April 1913. His father was a journalist with the Kent Messenger, his mother a schoolteacher, his maternal grandfather a dockyard worker. Shortly after Dick was born, the family moved to a slightly larger house in Maidstone, with a few feet of garden at the front, where Kenneth, who was killed in the last war, and John were born. All four boys went to the nearby Church of England School, All Saints, and, with the aid of scholarships, to Maidstone Grammar School whence Geoffrey, the eldest and Dick went on to the Imperial College of Science & Technology in London where they earned 1st class degrees in physics while the younger brothers equally distinguished themselves at Downing College, Cambridge. In the 1930s, one can understand only too well the sacrifice that had to be made by parents to support such ability, for money was very tight indeed but all four sons understood and deeply appreciated what was being done for them.

At the Grammar School three of the boys were cricketers, loved the game and played in the 1st XI. Not so Dick, he was just not interested; indeed it was a nine days wonder if he connected with the ball at all! He preferred to be out in the country, walking and talking with a friend. This was a characteristic that never left him for he always had a liking for discussion, either singly or in small groups. Nevertheless, he became a prefect, dominant in a quiet and thoughtful way but one that was not necessarily popular with boys who admired 'swashbuckle' and the charismatic leadership of the games player.

Beeching stayed on at Imperial College and gained his PhD (London) for research under Sir George Thomson. He continued in research until 1943, first at the Fuel Research Station in Greenwich and then at the Mond Nickel Laboratories in Birmingham where he was senior physicist concerned with a combination of physics, metallurgy and mechanical engineering. By 1938 he was becoming relatively affluent and married Ella Tiley, setting up home in Solihull. They had known each other from their schooldays and, although they did not have any children, they made up for it in many other ways. Ella complemented her husband perfectly, enjoying to the full the social life that came their way in later years and enabling him to relax at home. They had 46 immensely happy years together.

Although as a young man Dick is remembered

as quiet but brilliant, though with a sense of fun and humour.

Although as a young man Dick is remembered

as quiet but brilliant, though with a sense of fun and humour.

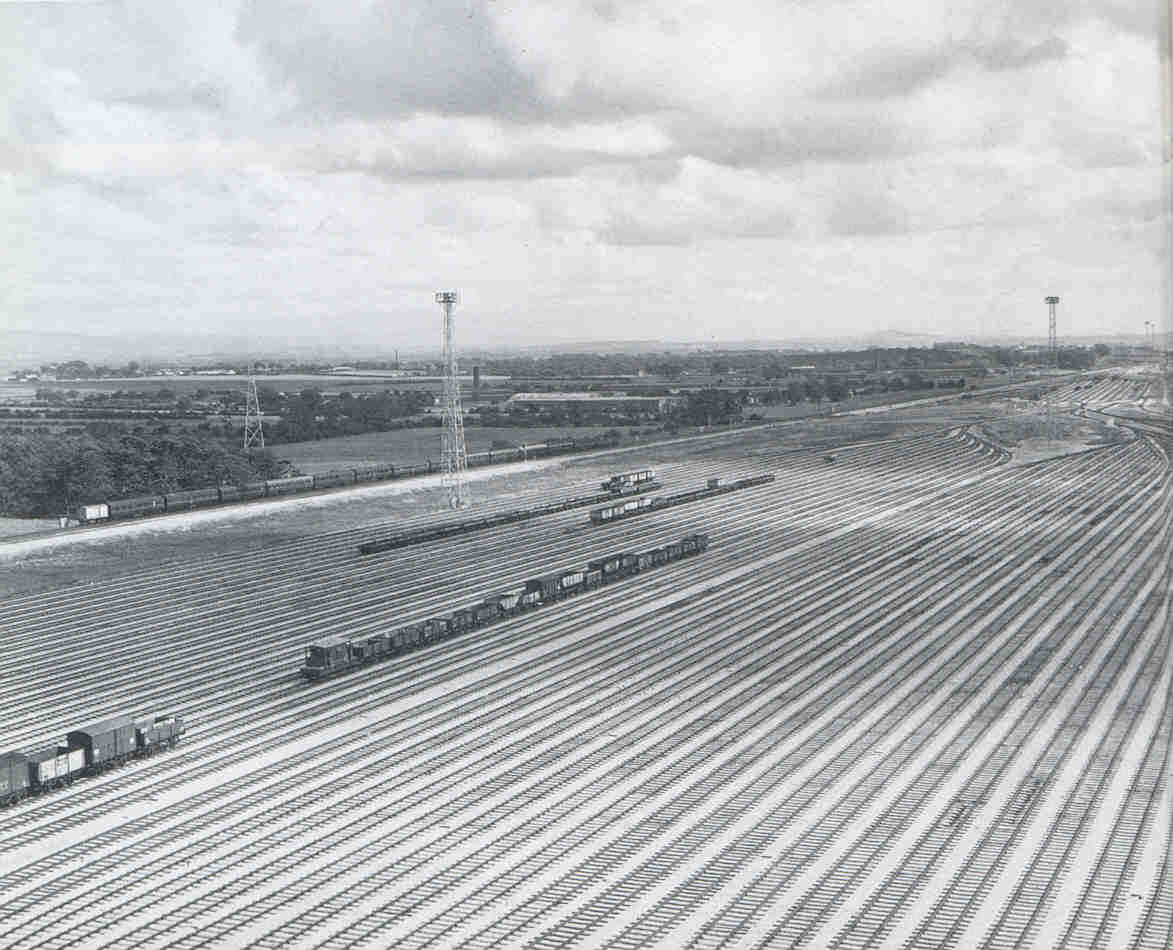

Whitemoor Up Yard was at March in the Fens - first gravity sorting yard in the country to be fitted with retarders - 1927

I doubt whether the family as a whole realised the enormous potential in their midst that was waiting to be developed, for he did not talk much about his work to his brothers. On the other hand, his mother, to whom he talked a great deal, was probably aware of something more than mere brilliance and, in later years, with great pride and enjoyment she became the 'distribution centre' for the rest of the family.

In the middle of 1942, at the height of the war, a committee under Sir Henry Guy recommended a recasting of the Ministry of Supply's Armament Design and Research Departments for the three fighting Services. Until then, design had depended on a design office staffed entirely by civil servants with management at all levels by officers from the Services, with the Head of the Department selected from each in rotation. Following the report, the management was now to be opened to civilians and service officers alike.

The first step was the appointment of F. E. Smith as Superintendent and Chief Engineer of Armament Design (CEAD). He had been a gunnery officer in World War 1 and as Chief Engineer of the Billingham Division of ICI he had already been closely involved with the war effort. When rearmament started in 1937, he was responsible for the design and building of government factories to make basic chemicals for explosives and for the production of high octane aviation petrol. In 1941 he was involved with the development of the Blacker Bombard (an anti-tank weapon for the Home Guard), and in March 1942 with the design and production of a shoulder weapon and projectile capable of penetrating 4in of tank armour (the PIAT). [This PIAT weapon was, according to one WWII infantryman whose life depended on it, useless against all but the smallest German tanks - ed.] Smith was, therefore, already known to Adm. Sir Harold Brown, the Chief Supply Officer of the Ministry of Supply, who had knowledge of the type of work involved.

Smith quickly appointed a number of highly qualified and experienced people from ICI and asked his friends in industry for further candidates. Among these, Dr Sykes of Firth Brown recommended a Dr Beeching, then aged 29. He was interviewed and engaged, and thus began a close understanding relationship which continued until he became involved with the railways.

Beeching was appointed to the Shell Design Section, which was short of people with a knowledge of physics and metallurgy. His rank was equivalent to that of an Army Captain, but he quickly showed his ability to analyse, fundamentally, problems of the most varied type. Soon after Smith took over as CEAD, he introduced a system for assessing, every six months, the relative abilities of the entire staff of the Drawing Office and, shortly after, a rather fuller approach to all the officer grades, civilians and Service officers. These appraisals covered both the technical and managerial aspects of the work and Beeching was always among those heading the list.

At the end of the war, Smith returned to ICI as Technical Director and was replaced as CEAD by Cdr Steuart Mitchell RN (who had been Head of the Gun Design Section) with Beeching as his deputy. Beeching continued his analytical work over a wider field, including AA guns and small arms, with striking results, some of which are only now, in the 1980s, being adopted; for example, the reduction by some 30% in calibre of standard small arms.

Beeching's promotion, at the age of 33, to the post of Deputy Chief Engineer with a rank equivalent to that of a Brigadier was the remarkable appointment of an emerging and very remarkable man. The Armament Design Establishment was staffed by professional engineers but it must be remembered that Beeching was a physicist, not an engineer, and his impact at senior level on these very experienced and rather hard-boiled practical engineers was fascinating.

Beeching refused absolutely to accept a Service demand for any weapon design that sprang from tradition. His physicist's mind fearlessly questioned and probed the fundamentals and paid little attention to custom and tradition. At first his appointment was rather ridiculed, but the ridicule changed first to sheer awe, then to fascination and finally to great enthusiasm for the approach to engineering problems of a physicist with a very great intellect. These, in fact, are largely the words of Sir Steuart Mitchell, his chief, who could understand his brilliance as a thinker, a planner and a man who delighted in solving the near impossible.

Mitchell and Beeching were to achieve a great rapport, to be renewed years later when Beeching asked his former chief, recently retired, to join him at Marylebone to reorganise the railway workshops. The two men had one perennial argument which caused a great deal of amusement to others then and in later years. Beeching was completely sold on Einstein's distortion of time and the Theory of Relativity. Mitchell, small, wiry and tough, had been a midshipman in the Grand Fleet in 1918, ultimately becoming a gunnery expert and Inspector of Naval Ordnance, and was an intensely practical man. For this particular purpose, he knew little of Einstein and cared less, so that Beeching's arguments were countered by a derision and dogmatism that effectively undermined the normal bland calmness, discussion and dissection to produce heated, fierce and involved argument that got the good Doctor absolutely nowhere at all! After years of fruitless endeavour, he was forced to admit that there might just be some small element of doubt.

In 1948, Beeching joined ICI as Personal Technical Assistant to his old chief, now Sir Ewart Smith and who was Technical Director on the Main Board. Beeching was in this post for about 18 months and during this time was mainly concerned with analysing the size and type of orders in relation to production lines for products as diverse as paints, leathercloth and zip fasteners, in conjunction with the Divisional staff involved. These analyses led to a significant reduction in production costs. In addition, he helped to improve the system of rail transport of raw or finished materials in bulk. During this period Beeching was moved about to jobs of increasing importance, mostly of an analytical kind, but he always preferred to work on his own, and opted not to appoint staff to be trained in his methods. After this introduction to the company's activities and organisation, he was transferred to the Fibre Division for Terylene production and in 1953 was sent to Canada to take overall responsibility for the construction and operation of a Terylene plant in Ontario.

He was now 40, and his team of engineers and managers found him quiet but determined and utterly brilliant. One of this team was the Resident Engineer, Leslie Norfolk, who remained a friend for the rest of Beeching's life and found him absolutely straight, absolutely honest and very amusing, though at times pretty sardonic, gently smiling in matters of importance and capable of being relentless in an extremely firm but civil manner. In close business association he did not always inspire affection of a personal nature. Nevertheless, however developed the mutual understanding and warmth might be, if the subordinate let him down, he was for the high jump. Beeching had become a great delegator: he would say precisely what he required but did not tell people how to do it. But if the man to whom he had delegated a job did not measure up, he would want to know why and, if the reasons were entirely within the control of the individual, Beeching would take the hard decision without hesitation. And if he made a mistake - and this was rare - he would never duck from under, always taking the full responsibility.

In Canada he would chair meetings of his team who, after the manner of engineers and managers, would have their say, all of them forcefully, all of them convinced they were right, all basically in disagreement. Beeching would sit there, smoking a pipe, silent, unmoving, listening, maybe twinkling gently and would then, at the appropriate moment, call a halt. 'Right, gentlemen, we are going to do it this way...'. And that was that, no further argument. But his view was never a consensus, rather a product of his mind which rarely coincided with any of the views expressed. The trouble was that he was almost always right!

Leslie Norfolk would go to him with a serious difficulty and Beeching would listen with care. He would then reply with a smile: 'You've certainly got problems, Leslie, good day!' or maybe, 'Right, let's allow events to unfold'. Instant management was not his forte, and he rarely wanted an immediate solution to a problem. He knew that his staff were competent people, each responsible in his own field, and if there was no obvious route forward he would take the decision as he saw it. It was this and other great qualities that inspired loyalty and affection and his basic strength was that, given suitable technical backing and provided he had the facts, he was prepared to take a risk, however unorthodox and controversial.

On his return to England in 1955, he became Chairman of the Metals Division on Sir Ewart Smith's recommendation. He was by no means universally welcomed, but those who worked with him quickly recognised a talent that was particularly needed in what had become a rather traditional Division and who came to regard his performance as Chairman as a great stimulus. And so, within two years, in 1957 he was made Technical Director on the main ICI Board and to relieve Sir Ewart Smith who had also been a deputy Chairman since 1954. His analytical powers had become more formidable than ever and, in a lifetime of experience, Sir Ewart had never found anybody to touch him in this respect. But he was not necessarily the supreme manager for he had not yet been truly exposed to the industrial rough and tumble; nor had he, in his most senior positions in ICI, discovered and brought on many young men. His predecessor as Technical Director was outstanding in this capacity, so that comparison was not easy. It can fairly be said, therefore, that the development and management of people. As individuals, was not his strongest point, but I have already stressed the quality of his leadership which rested on objective analysis and scientific method.

Yet again, in 1960, fate was to intervene. Sir Ewart Smith, who had retired in 1959, was asked by Ernest Marples to serve on the Stedeford group to consider the parlous loss-making condition of the British Transport Commission. Sir Ewart declined, being fully occupied with other matters but, understanding Beeching so very well, strongly recommended him with his great ability to analyse problems of this kind.

Beeching impressed Stedeford and all those closely involved with his analytical examination of witnesses, time and again asking the crucial questions and gaining a mastery of the subject in an extraordinarily short time. But whereas on the Royal Commission on Quarter Sessions and Assizes he was Chairman and held a commanding position, in the Stedeford group he had to use his great powers of persuasion to get the group to conclude a report based on his thinking. At the same time, Ernest Marples, faced with a desperate situation and being a man of action, saw at once that Beeching was a potential chairman big enough to solve the problems of the railway and to prescribe the remedy.

Extracted from:

'It is a difficulty which we all face, including the Commission, of trying to trace exactly where the money is being lost... the Commission itself admits that it cannot say with any precision where the money has been lost. All we know for a fact is that large sums of money are being lost......to talk as some do of the plan we have for the railways as being one for closures, and for closures alone, is claptrap and drivel. It has a positive and constructive side to it and that is what I want to emphasise.' John Hay, Joint Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Transport

***

In Government circles, the railways were considered to be far from essential; a next-to-worthless Victorian encumbrance in the age of road transport. What was the point of paying for railway modernisation when roads were already under construction to carry ex-railway traffic? [The author appears to have missed the fact that the government was acutely aware of how essential the nation's railway network was since the crippling strikes of the 1950s had brought industry to a standstill and the government to their knees - ed.]

There was a genuine and rather naive belief that lorries would handle the nation's freight, the private car would look after personal transport, and road buses would more than suffice for those who could not afford (or chose not to own) a car. If the railways were to remain (and it was politically expedient that they should, in some form) the network would be cut to a size where profitability could be assured.

There had been an ongoing debate for many years as to whether certain railway maintenance and investment costs should be borne by the State. After all, the Government was pouring large sums into the construction of a motorway and trunk road network, why should it not pay to develop the railways as well? The railways were just as much a state network as were the roads: why should they be expected to operate profitably? The official reply was that the road system was effectively self-financing, receiving income from vehicle road fund licences and car and fuel taxes. But it was a contentious issue, for it was impossible even to prove whether the income covered the true cost of building and maintaining the road network, let alone other consequential costs.

According to the road lobby, the road "income" exceeded direct expenditure on construction and maintenance by a healthy margin. What it omitted to observe, however, was that income fell well short of covering the real cost, including pollution, accident damage, policing, hospitalisation and congestion. The National Council for Inland Transport, a generally pro-rail pressure group, later attempted to estimate the real cost of the road network and came to the conclusion that the annual roads income of £610 million covered no more than half the true expenditure of about £1,486 million. The shortfall of more than £800 million exceeded the railway deficit man)~ times over, but such arguments were lost on a Government that openly favoured the road lobby.

Had the Government paused for a moment in 1960, weighed up the relative worth of various forms of transport, and reached the conclusion that individual roads should be placed under the same financial constraints as individual railways, the vast majority of minor roads would have been deemed uneconomic. The density of road traffic was spread just as unevenly as rail traffic, for half the vehicles were travelling on five per cent of the road network, leaving much of the system "uneconomic" in straight financial terms. The fact remained, though, that the railways were deemed a secondary, duplicate means of transport and, to Mr Marples, a Minister with a substantial interest in road construction, the answer was obvious.

The first, and probably the most difficult, task was to win the public relations battle, for an attempt to close a large proportion of the railway network was a policy that would cost the Government dear if it was handled badly. The message would be a simple one: that sacrifices would be needed by a few in the interests of the nation as a whole.

It might still have been an uphill struggle had the Government not brought out its big guns from the very beginning. It was decided that the Prime Minister himself would launch the campaign and on March 10, 1960, introducing a debate on the Guillebaud Committee report on railwaymen's wages, Harold Macmillan delivered a suitable speech:

'The carriage of minerals, including coal, an important traffic for the railways, has gone down. At the same time, there has been an increasing use of road transport in all its forms...

First, the industry must be of a size and pattern suited to modern conditions and prospects. In particular, the railway system must be remodelled to meet current needs, and the modernisation plan must be adapted to this new shape...

Secondly, the public must accept the need for changes in the size and pattern of the industry. This will involve certain sacrifices of convenience, for example, in the reduction of uneconomic services.. .

The public has to accept that it cannot ask the industry to take on some of the old functions such as fell upon a common carrier, and some of the old restrictions which were quite reasonable when the railway was a monopoly, of which there are signs still, and it must also accept the inconvenience of certain lines being closed and other means of transport being made available.'

The public had been told "to accept" it. There was an authority behind the voice of the Prime Minister that made the thing seem inevitable and, with the introduction of a few carefully worded slogans for the press, the campaign was well under way. One particular slogan gave the impression (without actually promising anything) that the Government was about to replace the outmoded railway network with a new improved version: "The railways are supposed to meet 20th century demands with 19th century equipment."

John Hay, Mr Marples' Parliamentary Secretary, generally put emphasis on the age and inadequacy of the railways, with remarks such as that "the existing system was laid down for horse-and-cart delivery and collection". Such remarks were deliberately intended to clear the way for a programme of railway closures.

Other claims were more defensive, such as Mr Marples' own Parliamentary reply that "traffic is going onto the roads because the people wish it to go onto the roads; I am not forcing it!".

Another slogan that caught the attention of the press was an implication that closures would increase road congestion by no more than one per cent, equivalent to two months' normal traffic growth. This claim was quite false, being based upon a most dubious accounting procedure, but it was widely quoted.

The Government's big push centred on the outmoded nature of the railway network and the mounting losses. There were plenty of figures to play with, and the Government made good use of them: the Transport Commission was £353 million in the red by 1960; the Government had loaned £600 million; the overall railway deficit for 1961 would top £150 million, £160 million in 1962, and so on. Most spectacular of all were the near £2,000 million overall capital liabilities of the BTC. As £1,400 million of this was in the form of British Transport Stock, it was quite unreasonable to imply that such a figure represented a railway debt. To put the figures into perspective, the actual working deficit was running at around £60 million a year, against a gross national expenditure of around £7 billion, but these figures were given little emphasis.

The Government made clear its view that the losses were horrendous, and that they could only-be reduced by eradicating the lines that did not pay. There was no direct reference to the extent of the proposed cuts, however, and the newspapers and the public produced answers of their own. Typical was the view of Professor Gilbert Walker, of Birmingham University, writing in Westminster Bank Review: "Railway route mileage to be closed cannot be less than 60 per cent. The proposition may be as high as 80 per cent." Even The Times fell victim to the misinformation campaign, agreeing that "half of total track mileage and a very much larger proportion in Scotland, Wales, South-West England and East Anglia" would close. When the authorities released the actual proposals a few years later in the Beeching report, their conclusions looked mild and well reasoned in comparison with these inflated expectations.

The Government naturally encouraged the view that railway closures were only of local importance and usually of a "rural" nature. This had been largely true during the 1950s, as the Transport Commission lopped off a few minor branch lines, but the plans of the Marples regime were on an altogether different scale. There was suddenly a very real threat to the entire railway infrastructure, although the official line continued to be that of minor rural hardship; of the necessity to "sacrifice" the convenience of a few unfortunate individuals who might in future need to take the bus.

Government policy undoubtedly paid off. The public, the media and even the specialist press began to accept the view that the Transport Commission was making overwhelming losses, and that the losses were largely caused by the rural railways. The only conceivable answer would be to cut the network.

The Road Haulage Association was only too glad to assist in the campaign and, in April 1960, its journal, The World's Carriers, went for the railway jugular:

It is understood that the Government have already settled the principles of reorganisation, and it will be for the Board to work out their detailed application...

We should build more roads, and we should have fewer railways. This would merely be following the lesson of history which shows a continued and continuing expansion of road transport and a corresponding contraction in the volume of business handled by the railways...

A streamlined railway system could surely be had for half the money that is now being made available... We must exchange the "permanent way" of life for the ''motorway'' of life... road transport is the future, the railways are the past.

There was a lunatic fringe that took the whole thing even further. According to Colonel John Pye, Master of the Worshipful Company of Carmen:

...a look should be taken at the widths of pavements and, where possible, steps be taken to cut them down to widen the road space... there should be more control of pedestrians.

Strangely, no-one objected, for in the early 1960s the motor car could do no wrong. Many of the claims of the Railway Conversion League - a dubious amalgam of thinly disguised road interests which campaigned for railways to be converted into roads - were equally ludicrous. The railways certainly had few friends at the time, while the road lobby was becoming ever more powerful. And that, really, was the problem. The railways had already lost the public relations battle.

General Sir Brian Robertson, the BTC Chairman, desperately mustered his troops in a last-ditch manoeuvre to turn the tide: "Our aim must be to counterattack and not merely defend!" But it was too late -the old soldier and his gallant staff were buried beneath a welter of invective from the heavy artillery of the road lobby, the Ministry of Transport, and the Government.

In a few short years, the road interests had become sufficiently powerful to influence political events, making it virtually impossible for the Government, or any future government, to hold out against them. From this viewpoint, the question of whether there was, or was not, a conspiracy to crush the railways... and who might, or might not, have been involved, becomes irrelevant. The road transport machine, once it had gathered momentum, was to destroy every obstacle in its path. Whether it began to move. on its own accord - or was pushed - was no longer important.

Some people had once believed they could vote for Labour yet still keep Churchill as Prime Minister; many now believed that they could have motorways without losing the branch railway lines. The Government did nothing to dispel the illusion.